After

the Nephites, under Mosiah the First discovered Zarahemla, several of these

Nephites or their sons, traveled back into Lamanite lands to reclaim their

birthright in the City of Nephi under Zeniff, who became the first king of this

Nephite enclave. After settling down and renovating the buildings, walls, and

making the cities of Nephi and Shilom and land round about worth living in

again (Mosiah 9:8), Zeniff, a righteous leader, passed on, appointing his son,

Noah, to be the next king.

Unfortunately,

Noah, was

an extremely wicked man and heavily taxed his people, spending the money on

extravagances and wickedness. Under his leadership, the Nephites were full of idolatry and indulgences and Noah a wicked

monarch best known for his burning the prophet Abinadi at the stake,

eliminating Zeniff’s priests and replacing them with his own evil priests, and

subverting the laws. During his time, he presided over a wicked kingdom guided

by false priests, and as the scriptures proclaim, “Noah did not walk in the ways of

his father,” and he took many wives and concubines, set his heart upon wealth

and spent his time in riotous living.

Noah tried to create the physical

signs of civilization. With the people’s taxes, i.e., one-fifth of all they

possessed, he “built many elegant and spacious buildings; and he ornamented

them with fine works of wood, and of all manner of precious things. He didn’t

skimp on the palace or the temple, either, and like many kings and government

leaders in other ages of mankind, he used impressive monuments and elegant

facades to persuade the people that they were a wealthy and mighty kingdom. It

likely was also meant to have an impact on the lazy, non-productive Lamanites

now living nearby in Shemlon (an area today considered to be Chanapata).

In one instance, no doubt to protect

himself and his people from any surprise attack from the nearby Lamanites, Noah

had a large tower built next to the temple on a hill overlooking the valley. In

the prophet Alma’s descriptive words: “Noah

built a tower near the temple, yea a very high tower, even so high that he

could stand upon the top thereof and overlook the land of Shilom, and also the

land of Shemlon, which was possessed by the Lamanties; and he could even look

over all the land round about” (Mosiah 11:12).

This tower was so high that from its

top one could see into the surrounding valleys, including Shemlon, the land of

the Lamanites, no doubt where those Lamanites and the king went after vacating

the city of Nephi when Zeniff and the Nephites returned. Obviously, it was not

far away since it could be seen clearly from the tower on top of the hill Noah

constructed. From this tower, Noah could see Lamanite soldiers amassing for an

attack in time to alert the people to man their defenses. In order for this

tower to be high enough to spy into the “lands round about,” it would not have been

made of flimsy wood, but sturdy stone with steps that probably circled the

interior and allowed for quick access to the upper floor where lookouts could

be stationed. However, it seems likely that Noah allowed the tower to go

unmanned much of the time for little is said about it until one fateful moment.

This is

seen in one event, when king Noah, under attack by his own people, and being

chased at sword point by an officer of his own guard named Gideon, ran in and “got upon the tower which was near the temple, and

Gideon pursued after him and was about to get upon the tower to slay the king,

and the king cast his eyes round about towards the Lamanite land of Shemlon,

and behold, the army of the Lamanites were within the borders of the land. And

now the king cried out in the anguish of his soul, saying: Gideon, spare me,

for the Lamanites are upon us, and they will destroy us; yea, they will destroy

my people” (Mosiah 19:5-7).

Centuries

later, when Francisco Pizarro led his conquering Spaniards into the land of

Cuzco in Peru, South America, they were startled to find such opulence,

magnificent construction, and marvelous buildings, many of the conquistadores

and chroniclers claimed rivaled those of Seville and even Rome. They saw, on a

hill overlooking the city, three towers next to a large temple and fortified

complex. The main tower was high enough to overlook the entire land “round

about” and stood predominantly at the far end of the Valley.

Of

this fortress, the famous Quechuan-Spanish chronicle writer, Garcilaso de la

Vega once wrote: “This fortress surpasses the constructions known as the

seven wonders of the world. For in the case of a long broad wall like that of

Babylon, or the colossus of Rhodes, or the pyramids of Egypt, or the other

monuments, one can see clearly how they were executed. They did it by summoning

an immense body of workers and accumulating more and more material day by day

and year by year. They overcame all difficulties by employing human effort over

a long period. But it is indeed beyond the power of imagination to understand how

these Indians, unacquainted with devices, engines, and implements, could have

cut, dressed, raised, and lowered great rocks, more like lumps of hills than

building stones, and set them so exactly in their places. For this reason, and

because the Indians were so familiar with demons, the work is attributed to

enchantment."

He was not the only early chronicler that lauded

the building capabilities of the early Peruvians, and in trying to find out who

had built the numerous stone edifices in the region, the Incas told the

Spaniards that the “Ancient Ones” had done so long before the Inca came to

power.

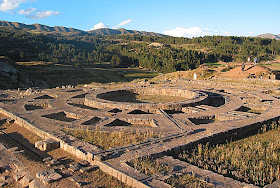

Not

discovered until 1934, when archaeologists began digging in the rubble

surrounding the area where the towers once stood, did they find the exact spot

where Garcilaso (left) claimed the towers had stood and began piecing together

the dimensions and ancient knowledge of the towers. They found in the center of

this area next to the temple, the very high cylindrical-shaped main tower that

had been erected in the center, which they called “Tower of Cahuide,” after the last Inca who died

leaping from it during a failed rebellion. Originally, it was called Muyuc Marca (Muyuqmarka), meaning “round precinct.” It should be noted,

however, that this is the name of the area or location, not the name of the actual

tower, though originally, it could have been both, for later, when the other two

towers were built, they were given separate names, but those names did not

relate to the area, only Muyuc Marca.

The

tower itself was a round building with an open central court which had a

flowing fountain. The overall tower stood 65-feet high and 12 feet around at

the base and narrowing to 9 ½ feet at the top, with four superimposed floors,

and a conic or cone-shaped ceiling—its amazing construction generated the

admiration of several early chroniclers. The view from the top, according to

Garcilaso was outstanding, and one could see over all the adjoining valleys.

The tower itself was painted in bright colors and had a thatched roof. Like

most of king Noah’s enterprises, it was not just built for function, but for

its impressive dimensions and manner of construction, meant to impress all who saw it.

A web-like pattern of 34 lines, which intersect at

the center, whose circular stone walls connected by a series of radial walls

made up the foundation base, which is all that is visible today and easily

observed by any visitor, as well as large enough to be seen by satellite. There

is also a pattern of concentric circles that corresponded to the location of

the circular walls.

It was at Muyu Marca where the strongest indigenous resistance occurred

against the Spanish conquerors during the rebellion of Manco Inca in 1536. Titu Cusi Huallpa (also called Cahuide), when the cause of rebellion was

obviously lost, jumped from Muyu Marca's

highest point to avoid being captured by his enemies. After the rebellion was suppressed

and defeated, the Spanish tore down the tower and all that is left is the

web-like pattern of foundation stones.

Garcilaso wrote that there were three towers at Muyucmarca, at the top of the walls.

These towers were built at equal distance from each other, forming a triangle.

The main tower was erected in the center and it was a cylindrical-shaped

one—larger and far more impressive than the other two, which were called Paucar Marca and Sallac Marca (or Sallaqmarca,

sometimes Sallaq Marka), and both had

rectangular-shaped bases.

Historians

are unaware of why the main tower was round and the other two rectangular,

however, it seems understandable that the first and larger tower was built by

Noah as the scriptural record tells us, and meant to impress, as indicated in

the statement that he: “built many elegant and spacious buildings; and he ornamented

them with fine work of wood, and of all manner of precious things, of gold, and

of silver, and of iron, and of brass, and of ziff, and of copper” (Mosiah 9:8).

The fact that it also served an important purpose for an early warning station

also suggests its rounded shape, what is considered today an inferior building

technique since round towers are considered less stable, though providing a better, and

unobstructed, view and why the lesser two towers were built rectangular.

However, its shape also must have been meant to impress, since the Spanish

found its design and construction so remarkable they lavished extensive praise

on it upon seeing the tower. Obviously, the other two must have been added later, even by later

generations.

It is interesting that no such tower,

with a view of adjoining lands, has ever been found among the numerous

constructions in Mesoamerica, and certainly not in North America.

No comments:

Post a Comment