The continental shelf is the

extended perimeter of a continent and associated coastal plain. Much of the

shelf was exposed during earlier periods, but is now submerged under relatively

shallow seas that are known as shelf seas and gulfs, and likely submerged

anciently.

A continental shelf is not seen above sea level, and is unknown to those who do not study

oceanography, except in principle; however, the shelf is actually part of the

continent and in the case of South America’s east coast, is rather extensive

Most continents are determined

by the range of the shelf about them, and some continents have little or no

shelf at all, particularly where the forward edge of an advancing oceanic plate

dives beneath the continental crust in an offshore subduction zone, creating a deep trough such as off

the west coast of Chile. The average width of a shelf is about 50 miles, and

though the depth of a shelf varies, it is generally shallower than 500 feet.

The slope of the shelf is usually quite low, and is basically the flooded margins

of the continent. Most of the coasts about the Atlantic have wide and shallow

shelves, made of thick sedimentary wedges, and ends at a point of increasing

slope called the shelf break, and the sea floor below the break is the

continental slope, followed the continental rise which finally merges into the

deep ocean floor, or abyssal plain.

Plate Movement is shown here with the Nazca Plate (left) running into

the South American Plate (right) along the Peruvian coast. This action takes

place from Colombia to the southern tip of Chile, as the Nazca Plate subducts

beneath (and lifting) the South American Plate

Because of the spreading,

contracting, subducting, slipping, etc., of tectonic plates, entire continents

move—today at a very slow rate, only a few millimeters a year; however, at

certain times in the history of the planet, they have moved much faster as is

evidenced by the division of the earth in Peleg’s time (about 2100 B.C.) and

the sudden rise of mountains, “whose height is great” indicated by Samuel the

Lamanite regarding the crucifixions of the Savior (about 33 A.D.) Geologists,

of course, do not accept such quick movement, but we know that it has and did occur

suddenly as it is written. In addition, we also know that when the flood waters

retracted, they did so suddenly, moving huge amounts of earth and creating

large canyons, gorges, breaks, valleys, etc.

As

can be seen by this diagram, when a tectonic plate (in this case, the Nazca

Plate) dives beneath another plate (South American Plate), the latter is lifted

upward since it has nowhere else to go

Scientists also tell us that

tectonic plates dive under one another, lifting the other, sometimes great

distances. This creates folds in the earth’s surface, mountains, and deep

channels in the seabed. All of this, of course, alters the visible land that is

seen above the surface, as well as that beneath.

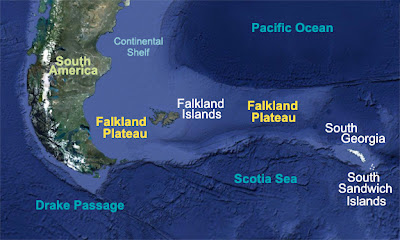

The Falkland Plateau, which is located

on a projection of the Patagonian continental shelf, would extend the area of

Patagonia eastward about 750 miles from Rio Gallegos in Argentina, lifting the

plate clear to the South George and South Sandwich Islands a thousand miles

beyond the Falklands

In the southeastern area of

South America, off the coast of Argentina, is the Falkland Plateau mentioned in

the last post. This plateau, or extension of the continental shelf, reaches as

far as the Falkland Islands (750 miles to the east, and also under other terms,

to the South Georgia Island and even the South Sandwich Islands about 1000

miles further east. That is to say, if the continental shelf around the

Falklands were to rise, which could happen from further subducting of the Nazca

Plate beneath the South American Plate, the continent of South America would

look something like a backward “S” rather than the shape we know.

This is far more likely than one might think due to the shallow depth of the basins surrounding the Falkland Islands. These three basins, if the Plateau were to rise as part of the continental shelf, would bring to the surface volcanic peaks in the west, a mountain range to the south, and an inner sea between the North Scotia Ridge and the current Falkland Islands area, with highlands at the north.

This is far more likely than one might think due to the shallow depth of the basins surrounding the Falkland Islands. These three basins, if the Plateau were to rise as part of the continental shelf, would bring to the surface volcanic peaks in the west, a mountain range to the south, and an inner sea between the North Scotia Ridge and the current Falkland Islands area, with highlands at the north.

Falkland Basins are bounded to the

west by the Falklands Platform, to the north by a steeply sloping feature

termed the Falkland Escarpment, to the east by the Maurice Ewing Bank and to

the south by the Scotia/South American plate boundary, which produces a

topographic feature known as the Scotia Ridge, which includes shallow water areas

such as the Burdwood Bank (immediately south of the Falklands), as well as the

islands of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

Whether or not such an event

should occur is unknown, though some scientists believe it might, at least at

some given time in the future. The point is that such movement upward of the

continental shelf has occurred in the past, tilting the entire eastern coast of

South America, to bring above sea level not only the Amazon Basin, but the

several other draining basins shown in the last post.

The problem is, it is a simple

matter for someone to write that South America was never under water, or that

the west coastal area, what is now called the Andean area, was the only basic

land above water, and scoff at the idea that the Land of Promise might have

been in South America; however, the facts of the matter are that the continent

of South America east of the Andes, even today, is barely above sea level. The

entire Amazon Basin lies between 400 feet above to actual sea level over a 2.7

million square mile area. Stated differently, when combined with a few other

contiguous basins, an area much larger than the United States, smaller only

than Russia, even today sits right at or near sea level on the continent of South America.

How can it be said that it was

always this way when hundreds of scientists studying the continent have

declared without a doubt that much of South America was once submerged?

(See the next post, “The Rising

of South America—Part VII—The Eastern Highlands,” to see the view of Guiana and

Brazil left after the sea withdrew from off the continent)

No comments:

Post a Comment