Continuing

with another comment from a new reader, evidently promoting his own book

“Finding Zarahemla,” to which we are responding and continuing with an

understanding of this entire Delmarva Peninsula that Franklin Reid claims was

the Land Southward.

Top Left: The peninsula—note how much

land there is beyond that is undefined and not collectable into a Land

Northward; Top Right: The peninsula divided between Delaware, Maryland and

Virginia, and described as “a flat narrow sandbar between the bay to the west

and the Atlantic Ocean to the east; Bottom: The marsh lands in the northern

Chesapeak Bay where Franklin places his narrow neck of land

The Delmarva Peninsula, originally known as the Delaware Chesapeake Peninsula or simply the Chesapeake Peninsula, acquired the name Delmarva shortly after 1859, but did not become widespread until the 1920s, is an

irregular coastline of drowned river valleys, streams, and creeks. The

terrestrial landscape is topographically low and consists of vast areas of

poorly drained silty soils and well-drained sandy soils. Large tracks of tidal

marsh now blanket former forests and fill former streams and creeks, creating

lowland swamps, floodplains, low terraces and inundated river valleys.

It might also be of interest to

know that during the last Ice Age, mile-thick glaciers stretched as far south

as Pennsylvania, and the Atlantic coastline was about 180 miles farther east

than it is today. Approximately 18,000 years ago, the glaciers began to melt,

carving streams and rivers that flowed toward the coast. Sea level continued to

rise, eventually submerging the area now known as the Susquehanna River Valley.

This drowned river valley became the Chesapeake Bay, which assumed its present

shape about 3,000 years ago (about the time of the Jaredites). Remnants of the ancient Susquehanna River still

exist today as a few troughs that form a deep channel along much of the Bay's

bottom. To fully define the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem, we must go far beyond its

shores. Although the Bay itself lies entirely within the Atlantic Coastal

Plain, its watershed includes parts of the Piedmont Plateau and Appalachian

Province.

Even so, the west coast of Dalmarva

has continually expanded and receded over the past three thousand years,

including the separation of islands from peninsulas, such as Tilghman Island

(Great Choptank) which formed only in the period not long before John Smith

discovered the area. In fact, just over 3,000 years ago, when the Jaredires

would have landed, no one knows exactly what the Chesapeake Bay looked like, or

even if it had yet formed, or that it extended far enough northward to reach

Franklin’s narrow neck of land to set ashore in the Land Northward. And what

would have brought their barges, being driven strictly by wave action, into the

bay against strong tidal currents—a mixed wave and tide energy that created the

lower seventy miles of the Virginia Eastern Shore tail on the peninsula. Of

course, the same thing could be said for Nephi’s ship, “which was driven forth

before the wind”—how did they go against the winds and currents streaming down

the Chesapeak Bay to empty into the Atlantic Ocean? And how did they land when the western shore of Delmarva was far too shallow to broach in a deep sea sailing vessel?

Even today, the Chesapeak Bay channel

is so flattened “fill up” sediment that an ship has to pass through 11 man-made

channels to sail up the Bay; near the mouth the channels are filling with sand

from the ocean, near Baltimore they fill with sediment from the land, requiring

a constant dredging program to keep the Bay and channels open.

In fact, 3,100 years ago, certain to be the

time of the Jaredite landings, geologists tell us that much of this southern

extension did not even exist above sea level (“Bay Geology,” Chesapeake Bay Program,

2012, Anapolis, Maryland). The area is shallow, and even today deep water ships

cannot dock anywhere along this southern extension of the peninsula, and

sailing ships of the type coming in from the open sea can not sail along the

east shore beyond Cape Charles, which northward is limited to barge traffic.

How Nephi’s ship could have landed along the middle of the peninsula would be

an interesting question to try and answer, since these depths on a nautical

chart show anywhere from 1 to 4 feet moving into the peninsula side of the Bay

(National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Nautical

Chart #12224-Chesapeake Bay, Cape Charles to Wolf Trap).

The Atlantic Coastal Plain is a

flat, lowland area with a maximum elevation of about 300 feet. To fully define

the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem, we must go far beyond its shores. Although the

Bay itself lies entirely within the Atlantic Coastal Plain, its watershed

includes parts of the Piedmont Plateau and Appalachian Province. The waters

that flow into the Bay have different chemical identities depending on the

geology of where they originate. This coastal

plain is supported by a bed of crystalline rock covered with southeasterly

dipping wedge-shaped layers of sand, clay and gravel. Water passing through

this loosely compacted mixture dissolves many of the minerals. The most soluble

elements are iron, calcium and magnesium.

The coastal plain extends

westward from the continental shelf to a fall line that ranges from 15 to 90

miles west of the Bay. Waterfalls and rapids clearly mark this line, which is

close to Interstate 95.

Cities like Baltimore, Maryland;

Washington, D.C.; and Richmond, Virginia, were built along the fall line to

take advantage of potential water power generated by the falls. These cities

became important commerce areas, as colonial ships could not sail past the fall

line and had to stop to transfer their cargo to canals or overland shipping.

Since its formation, the Chesapeake Bay's shoreline has

constantly been shaped by tides and currents that erode the land and move

sediments to other parts of the Bay.

There are many examples of erosion and sedimentation

throughout the Bay. As an example, some geologists

estimate that the Calvert County, Maryland, cliffs Captain John Smith explored

in 1607 and 1608 have eroded back 300 feet. By the mid-1700s, forests were cut

down and turned into farm fields, which increased erosion and caused sediment

to fill some navigable rivers. Joppatowne, Maryland, was once a sea port, but

is now more than two miles from water.

In addition, many

Chesapeake Bay islands that existed during colonial times are now severely

eroded or completely submerged. In the early 1600s, Maryland’s Poplar Island

encompassed several hundred acres. By the 1940s, only 200 acres remained. Today,

the area is being restored using dredge material from Baltimore Harbor.

The

State of Delaware is located within two physiographic provinces, the

Appalachian Piedmont and the Atlantic Coastal Plain. Most of the state lies

within the Coastal Plain; it is only the hills of northern New Castle County

that lie within the Piedmont (foothills). Delaware’s rolling hills, north in

the Twelve-Mile Circle, which rise to over 400 feet above sea level, are a part

of the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. The rocks at the surface in the

Piedmont are old, deformed, metamorphic rocks that were once buried in the core

of an ancient mountain range. This range formed early in a series of tectonic

events that built the Appalachians between about 543 and 250 million years ago.

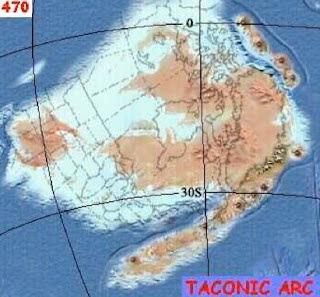

During an early event, called the Taconic orogeny, an offshore chain of

volcanoes collided with the ancient North American continental margin to push

up a gigantic mountain range that was as tall as the Alps or the Rockies of

today.

Geologists

date the Taconic orogeny between 470 and 440 million years ago. The Taconic

orogeny is important to our understanding of the geology of Delaware, because

during this event, the rocks of Delaware’s Piedmont were deeply buried under

miles of overlying rock and metamorphosed by heat from the underlying mantle.

Since that time, rivers and streams have carried the erosional products, mostly

sand, clay, and gravel, from the mountains onto the Atlantic Coastal Plain and

continental shelf. As the mountains wear down, the buried rocks rebound and

rise to the surface. Thus what we see in the Piedmont today are old, deformed,

metamorphic rocks that were once buried deep within an ancient mountain range.

Today, these mountain ranges are far out to sea.

(See the next post,

“Looking for Zarahemla-Part IV,” for more information on Franklin Reid’s book Finding Zarahemla, and his comments to

us and our responses, and also and introduction into the Dalmarva Peninsula to

show how it simply does not fit the scriptural record)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment