These gaps, of course, remain because of the limited recorded history the Valdia and later the Inca kept. In 1463 the Inca warrior Pachacuti and his son Topa Yupanqui began their conquest of the North—what is today known as Ecuador. By the end of 15th century, despite fierce resistance by several Ecuadorian tribes, Huayna Capac, Topa Yupanqui’s son, conquered all of Ecuador.

The unconquered areas, free from Incan and Spanish invasion

The area of pre-Columbian Ecuador included numerous indigenous cultures, who thrived for thousands of years before the ascent of the Incan Empire. It is interesting that scientists today want to make claims about the origination of cultures, or tribes, or nations, but the fact is there is little, if any, historical knowledge to suggest this—merely stories, myths and legends handed down for generations.

In fact, when Pre-Columbian Cultures are mentioned, it refers to the indigenous people bound in various tribes, that lived in America before the arrival of Columbus. It should also be noted, that the Americas has a history of thousands of years prior to the arrival of the Europeans. While anthropologists and archaeologists do not refer to these earlier people that inhabited pre-Columbian America as tribes, calling them ethnic group cultures, what we know of their history does not disqualify the name tribe, which is a social division in a traditional society consisting of families or communities linked by social, economic, religious, or blood ties, with a common culture and dialect, typically having a recognized leader.

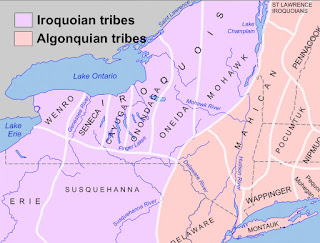

They were known during the colonial years to the French as

the Iroquois League, and later

as the Iroquois Confederacy, and

to the English as the Five Nations,

comprising the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca

Further West were the Sioux, who were broken into separate tribes or nations as the Yankton, Oglala Lakota, Rosebud, Sicangu Lakota, Upper Brulé, all in what is now South Dakota. There were also the Arikara, Pawnee, Apache, Comanche, Choctaw, Cree, Ojibwa, Navajo, Blackfoot, Seminole, Hopi, Shoshone, Mohican, Shawnee, Mi’kmaq, Crow, Paiute, Ute, and numerous others. Many of these groups were similar, and many others descended from the same group

Anthropologists and Archaeologists, and even modern Native American Nations, can claim whatever background, combination or separation they choose; however, the fact of the matter is that at some time in the past most, if not all, of these various tribes, nations or peoples, descended from common ancestors.

At the time of the European movement into the Americas, the lands we call today North and South America, housed numerous groups, which anthropologists and archaeologists have divided and sub-divided into cultures. The one thing they all had in common from the perspective of the invaders was that these people were “primitive,” with totally unacceptable religions and beliefs. Only the Inca, Aztec and Mayan had achieved enough in their time to qualify for advanced societies or cultures.

Yet, the fact is that the original peoples of Andean South America achieved skills and accomplished such results that even today, modern man has not equaled some of their more remarkable achievements. And when we compare their achievements on a time scale with that of Europe, Asia and Africa, only Rome had achieved similar accomplishments in many ways.

Some of these groups were isolated, and developed their own style of dress, artistic expression, spiritual beliefs, and even language—but so many of their traits and characteristics were so similar that it is difficult to continue the claim they were separate cultural groups. The fact that one area made pottery different from another (one of the major divisions of cultures for anthropologists and archaeologists) does not make them different people from different backgrounds.

After all, in the United States in the mid19th century, the division of work, achievements, interests, and overall accomplishments between the Northern States and the Southern States was remarkably different—one was technologically superior to the other, out of necessity. That is, the northern soil and climate favored smaller farmsteads rather than large plantations. Industry flourished, fueled by more abundant natural resources than in the South, and many large cities were established; while the fertile soil and warm climate of the South made it ideal for large-scale farms and crops like tobacco and cotton. Because agriculture was so profitable few Southerners saw a need for industrial development. Eighty percent of the labor force worked on the farm. Although two-thirds of Southerners owned no slaves and only one tenth of the population lived in urban areas.

The distribution of the earliest Ecuadorian

cultures, mostly along the coastal area and slightly inland

According to Alexander Hirtz, head of the Charles Hirtz Foundation, is a native of Quito, Ecuador, where he grew up and was continually exposed to the traditions and knowledge handed down from generations going back thousands of years. His father spent decades living with the indigenous culture and collecting their traditional artwork, with Alexander spending a great deal of time and resources researching the cultures, their symbols, and their knowledge—virtually every major civilization of the tropical Americas before the Spanish conquest. He has served as the Director of exploration of Ecuadorian and Peruvian precious metals fields, Director of Chamber of Mines of Ecuador, and Director of Geologic studies Ecuador, stated regarding the earliest Ecuadorian cultures, such as the Valdivia: “Seemingly out of nowhere, these civilizations show up bearing cultural advancements that must have taken thousands of years to develop. Moreover, these civilizations are remarkably similar; however, we are led to believe by modern science that they did not share a common origin. The going story is that they simply popped up, and we should just accept that.”

From his studies, Hirtz found that the Valdivians were a pre-Columbian culture from coastal Ecuador, who distinguished themselves for their sophistication earlier than 3,500 years ago (before 1500 BC), and outranked any other culture in America of that period. In this timetable, which apparently relates to the manufacture of fired ceramics, we can see that Valdivia predates by far the first culture in Mexico, the Olmec, by more than 1500 years and the Chavin, the first culture in Peru by 2000 years.

Ecuadorian archeologist Emilio Estrada with Betty Meggers and Clifford Evans of the Smithsonian Institution assisting with the excavations, discovered the first remains of this culture in 1956, in the fishing village named Valdivia, hence the name for the culture.

Valdivia verbal history states they

came from the east, landing in the area of Santa Elena Peninsula in southwest

Ecuador

Most current archeologists have rejected the theory of the Valdivian coming from the West, across the Pacific, but that they came from the East, from where they introduced to the mountainous area the knowledge of more advanced agriculture, bringing seeds of beans, coca, tobacco, cacao, cannas and other strains of maize, as well as plants with fibers for their textiles, like palm fiber, and pita, a bromeliad of the pineapple family.

(See the next post, “Ecuadorian Cultures Existing at the Time of the Jaredites – Part II,” regarding the development and historic events in Ecuador at the time of the Jaredites, and later the Nephites)

I didn't think the Huron were great friends with the 5 nations but I'm getting older the memory may be bad

ReplyDeleteI am just about 99 % sure the Cherokee were mortal enemies of the iroquois and it wouldn't matter except to a cherokee!

ReplyDelete