It is interesting that in both the Heartland and Great Lakes theories of North America, there is little or no mention of the Jaredite lands—only that they were vaguely to the north. In the Great Lakes Theory, they were in Canada, but no detail of any kind are shown. In fact, with both the Heartland and Great Lake theories, there is no Land of Many Waters on their maps, though they all have the hill Cumorah in Western New York, but nothing else about the Jaredite lands. Nor do they show the location of the capital city of Moron, or how enclosed barges made it to Canada, nor where they landed.

It might also be interesting to know that these theorists of the Heartland and Great Lakes models locate, at most, a Land of Desolation, some claiming that the Land Northward had only the Land of Desolation in it; however, the scriptural record tells us: “Now the land of Moron, where the king dwelt, was near the land which is called Desolation by the Nephites (Ether 7:6, emphasis added). This tells us there was at least one other land, and probably more in the Land Northward—certainly there was a Land of Many Waters and a Land of Cumorah (Mormon 6:4).

The Grand Banks are a series of underwater plateaus southeast of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf

Heartland theorist Theodore Brandley stated in 2015 that in his “Journey of the Jaredites” that they landed in what is now New Jersey. Vernal Holly claims the Jaredites were in lower Ontario just north of Lake Ontario.

Other theorists suggest the possibility that the Jaredites might have fished off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, believing the barges reached the St. Lawrence River. This is based on some claims of evidence that the Grand Banks Newfoundland had evidence of fishing long before any Europeans were in the area.

Officially, this area was “discovered” by the Norsemen in 1001 AD, when a flotilla of Viking ships set sail from Greenland southwestward they reached Labrador, which they called Helluland (“Land of Rocks”), they proceeded for two days more and reached the west coast of Newfoundland, a shore with sandy soil covered with pines and birches where they saw many animals. This was Newfoundland which they named Markland (“Country of Forests”).

They continued down the coast, which they traced to the west, and landed in a region with rich vegetation where maize and wild vines grew in abundance and the fresh water swarmed with salmon. This country, which they called Vinland (“Lands of the Vine”), which was the coast of Massachusetts. They landed on Cape Cod, probably where Boston sits today.

1001 AD Viking settlement in L’Anse aux Meadows on the northernmost tip of the Great Northern Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador

The Vikings maintained colonies in the regions which are today Labrador, Nova Scotia and Massachusetts until the 12th century—the settlements were probably to exploit natural resources such as furs and in particular lumber, which was in short supply in Greenland. Historians say it is unclear why the short-term settlements did not become permanent, though it was in part because of hostile relations with the indigenous peoples, referred to as Skraelings (Eskimos of Greenland and Vinland) by the Norse. Nevertheless, it appears that sporadic voyages to Markland (Newfoundland) for forages, timber, and trade with the locals could have lasted as long as 400 years. The point is, before Columbus and the later Spanish and Europeans, the Americas were not settled by any permanent emigrant group of which we know.

There is, of course, evidence, though scant, of these events, and of the Vikings in the area of the Grand Banks off Newfoundland. This area is one of the world's richest fishing grounds—the shallow waters mix with both cold water of the Labrador current and warm water from the Gulf Stream, that make an ideal breeding ground for the nutrients that feed the fish, supporting Atlantic cod, Swordfish, Haddock and Capelin, as well as shellfish, seabirds and sea mammals.

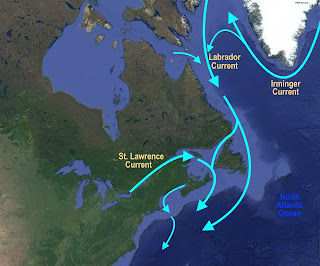

These currents run down the St. Lawrence from Lake Ontario to the St. Lawrence Gulf and join with the Labrador Current flowing southeast through the Davis Strait and into the Labrador Sea and finally into the North Atlantic Ocean going south along the coast of New Brunswick and Main—in the opposite direction from win-driven ships or barges heading northward along these coasts. All of this would work against any wind-driven ship, or the barges built by the Jaredites reaching these Banks.

Ocean Currents that Jaredites would have had to go against to reach the area of Newfoundland

The Banks, which are located on the southern tip or "toe" of the Burin Peninsula (also known as "the boot"), extend for 350 miles north to south and for 420 miles east to west, are the result of extensive glaciation that took place during the last glacial maximum. When the majority of the ice had melted, leaving the Grand Banks exposed as several islands, which extended for several hundred miles. It is believed that rising sea-levels submerged these, which is what we see today. This entire area is relatively shallow, ranging from 50 to 300 feet in depth, with an average of 180 feet.

The Grand Banks consist of a number of separate banks, chief of which are Grand, Green, and St. Pierre; and sometimes considered to include the submarine plateaus that extend southwestward to Georges Bank, east-southeast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The cold Labrador Current mixes with the warm waters of the Gulf Stream in the vicinity of the Banks, often causing extreme foggy conditions.

The mixing of these waters and the shape of the ocean bottom lifts nutrients to the surface, which creates one of the richest fishing grounds in the world. It certainly would have provided an excellent area in which to fish at the time of the Jaredites, however, placing them that far north is very unlikely.

While no archaeological evidence for a European presence near the Grand Banks survives from the period between the short-lived Greenland Norse settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in 1000 AD and John Cabot’s transatlantic crossing in 1497, some evidence suggests that voyagers from Portugal in the Basque Region and England proceeded Cabot.

In the 15th century some texts refer to a land called Bacalao (“Land of codfish”), which is possibly Newfoundland. Within a few years of Cabot's voyage the existence of fishing grounds on the Grand Banks became generally known in Europe. Ships from France and Portugal pioneered fishing there, followed by vessels from Spain, while ships from England were scarce in the early years (Kirsten Seaver, Maps, Myths, and Men: The Story of the Vinland Map, Stanford University Press, 2004, pp75-86).

The Jaredites landed along the shore of the Land of Promise and went upon the land and settled, tilling the earth (Ether 6:12-13). At some point they moved up into the highlands or mountains and built a city named Moron, and when Corihor, son of Kib, rebelled against his father and dwelt in the Land of Nehor where he raised an army, and “he came up unto the land of Moron, where the king dwelt” (Ether 7:5, emphasis added). Later, when “the Lord warned Omer to depart out of the land, and he traveled many days, and came over and passed by the hill of Shim, and came over by the place where the Nephites were destroyed, and from thence eastward, and came to a place which was called Ablom, by the seashore” (Ether 9:3,emphasis added).

Thus, we see that the Jaredites were to the north of the Narrow Neck of Land, and Many days travel from Moron to reach the Hill Cumorah, which itself was to the north of the narrow neck and some distance to the west of the seashore.

Obviously, the configuration here stated is that the Hill Cumorah was to the north, for Omer turned east from the Hill Cumorah. You cannot turn east when traveling east from the beginning (which eliminates both Mesoamerican and North American theories) and you cannot turn east when going west except to double back on your westward route. You could turn east when going south, but that would place the Hill Cumorah across into the Land Southward.

In addition, in the North America theory, traveling from the Narrow Neck of Land east to the Hill Cumorah is 100 miles. However, from there to Newfoundland is 725 miles—hardly a workable arrangement according to the scriptural record. Nor is it better to travel east to the sea from the Hill Cumorah, a distance of 370 miles. In Meldrum’s Heartland, he has The Hill Cumorah 865 miles to the east of Nauvoo, Illinois, and another 370 miles eastward to the sea. His East Sea is to the north of the Hill Cumorah.

Neither the North American theories (Heartland or Great Lakes) nor the Mesoamerican theory matches the simple description of the scriptural record and should be disqualified on the basis of this alone.

There was an early Massachusetts historian that wrote about the Viking community called Norumbega. An interesting book telling of early English settlers observations of remains of

ReplyDeleteViking works in their area. I should try to find that old book. I read it years ago. Very interesting stuff.