Comment #1: “Why was the city of Nephi later called the city of Lehi-Nephi, or are these two different cities?” Wanda T.

Response: A simple answer is, “no,” they are the same city, and we do not know why the name of Lehi was added later. However, we might surmise a reasonable answer—first of all, the major cities in the Land of Nephi were Nephi (later called Lehi-Nephi), Shilom, Shemlon, Ishmael, Middoni, Lemuel and Shimnilom. It is probably safe to assume that the city of Jerusalem was in the same area. Secondly, the initial area of Lehi’s landing was called the Land of Lehi (from the lost 116 pages) and the “place of their father’s first inheritance” (Alma 22:28).

After Lehi’s death, Nephi was told to flee into the wilderness with “all those who would go with” him (2 Nephi 5:5) to escape his brothers who sought his life (2 Nephi 5:4). He settled any area, evidently quite some distance away, and likely northward since the Nephites were always to the north of the Lamanites (Alma 22:33). Nephi several of the original party of Lehi with him when he fled into the wilderness (2 Nephi 5:6-7), and when they settled, the people “would that we should call the name of the place Nephi” (2 Nephi 5:8).

This was the original City of Nephi, in the Land of Nephi. The Nephites remained in this general area, spreading out and after about 200 years, they had “multiplied exceedingly, and spread upon the face of the land, and became exceedingly rich in gold, and in silver, and in precious things, and in fine workmanship of wood, in buildings, and in machinery, and also in iron and copper, and brass and steel, making all manner of tools of every kind to till the ground, and weapons of war” (Jarom 1:8).

About 200 years later, the Nephites had become so evil that the Lord told Mosiah I “to flee out of the land of Nephi, and as many as would hearken unto the voice of the Lord should also depart out of the land with him, into the wilderness” (Omni 1:12), and were led northward into the Land of Zarahemla (Omni 1:13), where they settled among another people, descended from Mulek (Mosiah 25:2; Helaman 8:21), whom the Lord brought into the land north, and Lehi into the land south (Helaman 6:10).

While the scriptural record is vague about what happened to the City of Nephi after Mosiah left, evidently the Lamanites moved in and took it over, along with the surrounding cities especially Shilom and Shemlon. During the days of Mosiah’s son, Benjamin, a group of Nephites in Zarahemla returned to the Land of Nephi to reclaim the City of Nephi. Evidently, at this time the city was being called Lehi-Nephi, perhaps a name developed by the Lamanites who did not want to live in a city named Nephi. It is even possible that the Lamanites called it simply the City of Lehi, but Zeniff, the leader of these Nephites from Zarahemla, and his Nephite followers, applied the name Lehi-Nephi to make it as their city as well.

It should be noted that the Lamanite-controlled portion of the Land Southward was called the Land of Lehi (Helaman 6:10) and the Lamanites might have referred to themselves as Lehites. In addition, Zeniff, made a deal with the Lamanite king who moved himself and his people out of the city and that of Shimlon, and turned them over to the Nephites (for his own purposes which became obvious later on), but continued to occupy the city of Shemlon.

From this point on, the city is referred to as the City of Lehi-Nephi (Mosiah 7:1,21; 9:8), until it reverts back to the City of Nephi (Mosiah 9:15) and continues to be so called (Mosiah 20:3;21:1,12) until Alma and later king Limhi leave the city and make their way to Zarahemla.

After this, the city became the chief city of the Lamanite kingdom (Alma 47:20), and the Land of Nephi ran in a straight course from the Sea East to the west (Alma 50:8). This city of Nephi (Lehi-Nephi) was located in a valley surrounded by hills at a higher elevation than Zarahemla, from which it was separated by a wilderness, that evidently consisted of forest land, where wild beasts could be hunted (Enos 1:3).

The city of Nephi was probably situated between the Lamanite land of Shemlon and the wilderness, for when the Lamanites approached from the direction of the land of Shemlon, the Nephites fled into the wilderness, presumably in the opposite direction (Mosiah 19:9, 23). Earlier, Zeniff had the women and children hide in the wilderness when the Lamanites attacked (Mosiah 10:9). Similarly, when Limhi saw the Lamanites preparing to attack—probably from the land of Shemlon (Mosiah 28:1)—he sent the people into the fields and forests (Mosiah 20:8).

Comment #2: “How many ways is Sacsayhuaman spelled? I have yet to find the one correct spelling to which all adhere” Leonard M.

Top: Aerial

view of Sacsayhuaman. The circle in the middle is the tower base next to the

temple with the fortification on the other side and in the top is seen two of

the three zig-zag walls protecting the northern side with a cliff surrounding

the southern loop which overlooks the valley below: Bottom: A portion of the

lower zig-zag wall

Also, since the late 18th century, when Quechua was banned from public use in Peru in response to the Tupac Amaru II rebellion, the Spanish crown banned even loyal pro-Catholic text in Quechua, such as Garcilaso de la Vega’s Comentarios Reales. Currently, the major obstacle to the diffusion of the usage and teaching of Quechua is the lack of written material in the Quechuan language, namely books, newspapers, software, magazines, etc. Thus, Quechua, along with Aymara and the minor indigenous languages, remains essentially a spoken language, with adoption of Spanish for the purposes of social advancement.

It should also be noted that because of the modern tourist guide habit of making fun of the name to English-speaking tourists, by calling it “Sexy Woman,” it has acquired the spellings of Saksaywaman, Saqsaywaman, Sasawaman, Saksawaman, Sasaywaman or Saksaq Waman. In this blog, we often use the Anglicized version Sacsahuaman for brevity.

Comment #3: “Is there any indication that the ruins and ancient settlements in Ecuador, your land northward, are older than those of Peru, in your land southward?” Peter D.

Response: According to the experts in the field, the Manabi remains of Ecuador are exceedingly ancient, dating to around 1500 B.C.. Hyatt Verrill (left) said that these unknown, forgotten races of Ecuador were more remarkable, and were unquestionably far more ancient than the Incas, Aztecs, or the Mayas and the others” (Alpheus Hyatt Verrill and Ruth Verrill, America’s Ancient Civilizations, Putnam Sons, New York, 1953, p148); In fact, they add, “It would appear that the Manabis were a distinct race with a culture different materially from that of any other ancient people of South or Central America” (Alpheus Hyatt Verrill, Old Civilizations of the New World, New Home Library, 1942, p242)

Comment #4: “So many things in ancient Peru seem to be named puma. I have read that a puma is like a cougar. Is that true of the Nephite era?” Maryann W.

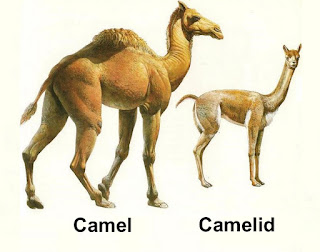

Response: It is true that most dictionaries define “puma” as a “cougar,” which is defined as a large American wild cat with a plain tawny to grayish coat, found from Canada to Patagonia.” However, “puma” was a Quechua word that meant “lion.” Garcilaso de la Vega, in his chronicles of Peru, claims the Andean “puma” is a “lion,” and much like the African lion, the males had manes and the females did not. Originally the word was evidently spelled “poma,” according to Johann Jakob von Tschudi (Fauna Peruana (Animals of Peru), St. Gallen University, HSG Publishing, Switzerland, 1844-1846, p126). It is also defined as “lion” by the Hakluyt Society,Vol V, London, England, p238)

The Puma is a genus in the family

felidae that contains the cougar (also known as the puma, among other names)

Early archaeologists tried to see the puma design in all things, from rock carvings to the layout of Cuzco, fitting the remaining round tower base on Sacsahuaman as “the eye of the needle.” Today, however, that is less likely indicated except by historians who have not understood this change.