Gardner: “It is both interesting and important to note that Mesoamericans were not the only peoples to use left/right rather than specific names for directions.

Response: It might surprise most to know that before the 12th century A.D., the English word “north” was defined as: “the direction that is to your left when you are facing the rising sun: the direction that is the opposite of south,” and referred to as “left hand,” or “on the left hand.” Many of us were we were taught this way as kids, with directions defined as “left” and “right.” In fact, in an old school book, the terminology was: “North: the direction to the left of someone facing east.” This is not just American, but also Hebrew—since they use east as their orientation (like we use north), their word for “south” is “teyman” which means “to the right.”

Gardner: “William J. Hamblin, professor of History at Brigham Young University notes: “The Hebrews, like most Semitic peoples, oriented themselves by facing east, toward the rising sun. Thus east in Hebrew was simply front (qedem), with south as right (yamîn), north as left (śemôl), and west as rear (achôr) or “sea” (yam).”

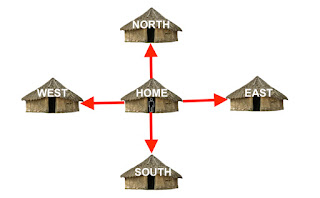

Response: The way in which ancients were taught or remembered directions is neither new or unique to eastern people. That they face, or orient themselves, to the east, where westerners face, or orient themselves, to the north, is neither important nor decisive in understanding cardinal directions. When most westerners were young, they were taught to face north, with the rising sun on the right and the setting sun on the left. Naturally, behind them was south. Like Hebrews/Jews, who had the Mediterranean Sea to the west (or behind them when facing east), being from Southern California, I had the Pacific Ocean to the west (my left when facing north).

When a

Westerner faces North to orient himself, West is on the right hand; When one in

the middle East faces East to orient himself, North is on the left hand. It

would not matter what words are conveyed to state this, i.e., right hand, right

side, right leg, etc.

Gardner: “The Egyptians oriented themselves by facing south, toward the source of the Nile. “One of the terms for ‘south’ [in Egyptian] is also a term for ‘face'; the usual word for ‘north’ is probably related to a word which means the ‘back of the head.'” The word for east is the same as for left, and west is the same word as right.”

Response: This point is taken from William J.Hamblin, in Direction in Hebrew, Egyptian, and Nephite Language, in Re-exploring the Book of Mormon edited by John W. Welch of FARMS. Again, these are strictly Mesoamerican points. Once again, the point should be made that while Easterners looked to the East for their orientation, Westerners look to the North for their orientation, the Egyptians and Chinese looked to the South for their orientation. This orientation is seen in which direction is at the top of their maps, which shows a proclivity toward how they think. It is also important to know and understand that how words originally came into being has almost no meaning on how they are seen, used, and interpreted in later generations.

Our “north” is from Old English “northr,” Dutch “noord,” and High German “nord.” Chances are, most English-speaking people have never heard of these words. One of the early meanings of “north” was “above” or “overhead,” One of the early definitions of “north” is “to the left of a person facing the rising sun.” It is “0” on a degree compass, can depict a “north wind,” meaning it is not blowing toward the north, but blowing away from the north.

In fact, you can look up the etymology of just abut any word and it has derived from a meaning or source one didn’t know about; consequently, it had been numerous generations since Nephi had to face east with his back to the sea to determine his directions. The idea of quoting word origination to prove a point of Nephite directions is both silly and meaningless.

Gardner: “It is worth emphasizing that our Book of Mormon is the result of Joseph Smith’s translation. The nature of that translation has been the subject of discussion among faithful scholars, with opinions ranging from Brigham H. Roberts’ declaration that Joseph “had to give expression to those facts and ideas in such language as he could command” to Royal Skousen’s understanding that Joseph Smith precisely read a translation that had already been done and which appeared in some manner when using the interpreters. My own analysis of the available data is more in line with Roberts.”

Response: Gardner makes it sound like an either or condition with Joseph Smith’s translation and, interesting enough, but not inconsistent with Mesoamerican theorists, no mention of the role of the Holy Spirit is mentioned. However, let’s take these three points one at a time:

1. Joseph had to give expression to those facts and ideas in such language as he could command. While it is true that Joseph was limited to his knowledge, vocabulary, and expression of his own language, and it is also true that the Lord “speaketh unto men according to their language, unto their understanding” (2 Nephi 31:3), it would be wrong to believe that Joseph had to figure everything out on his own. This is seen in the Lord’s comments to Oliver Cowdery, who was not content to merely serve as Joseph’s scribe—he wanted to translate himself. President Joseph Fielding Smith pointed out that “it seems probable that Oliver Cowdery desired to translate out of curiosity, and the Lord taught him his place by showing him that translating was not the easy thing he had thought it to be.”

Obviously, translating was not merely an act of sitting back and waiting for the words to come to mind, but required work and effort on the part of the translator. Why did Oliver fail? The Lord assigned Oliver’s failure to translate to the fact that he did not translate according to that which he desired of the Lord. Oliver had to learn that translating as Joseph Smith was doing was by the gift and power of God. Evidently, Oliver had received sufficient instruction, but instead went his own way, using his own wisdom. He was therefore stopped from translating. As the Lord told him: “You have not understood; you have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought save it was to ask me” (D&C 9:7). The Lord then went on to tell Oliver, “You must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right, and if it is right I will cause that your bosom shall burn within you; therefore, you shall feel that it is right.” (D&C 9:8).

Thus, it should be understood that Joseph had to put out effort, had to study it out in his mind, then see if it was right, and if so, he then read it off to his scribe, but if it was not correct, the wordage did not disappear and Joseph had to work at it again.

(See the next post, “The Mystifying Rationale of Mesoamerican Directions – Part XVI,” and the continuation of Gardner’s rationale of the Mesoamerianists’ skewed Land of Promise, and the various meanings of words that Joseph Smith used in the translation and their accuracy, and with Royal Skousen’s comments)