The Forgotten History: Father Crespi and the True Legacy of the Americas

My father’s office was a treasure trove of knowledge. The

shelves were filled with books on Central and South America—works by the big

names in North and Central American theories, but also obscure records and

firsthand accounts that most researchers overlooked. Among his prized

possessions were his carefully compiled books on the Spanish chroniclers. These

were the men who gave us glimpses of a history that was otherwise lost—the

unwritten story of the Americas from the end of the Book of Mormon to the

arrival of the Spanish conquistadors.

For the Lamanites, record-keeping in written form was not

their strength, and what little remained of Nephite history was annihilated in

their final destruction. The Spanish brought with them the ability to record

history in ways that modern readers could understand. But the irony is

inescapable: the very conquerors who documented the marvels of the New World

were also the ones who destroyed those marvels, burning records, melting down

sacred artifacts, destroying and looting sacred sites and erasing entire cultures in their lust for conquest and

wealth.

The 1500s had no photographs, no videos—only the written

word and the art left behind. The Spanish chroniclers, often working under the

shadow of destruction, became the last witnesses to a history that was

vanishing before their eyes. Their accounts give us invaluable insights into

what was once there—temples, treasures, and traditions—but always filtered

through the lens of their own biases and agendas.

This is the lesson we must learn: the true history of the

Americas has been stolen, repurposed, plundered, hidden, and distorted. And few

examples illustrate this better than the story of the Father Crespi collection.

Tragically, the Crespi story is not unique but is one of many accounts of

powers conspiring to keep the true history of these lands hidden. Allegedly the

artifacts in Father Crespi’s collection threatened established narratives—those

of Ecuadorian history, South American history, and even the Catholic Church

itself. These are formidable forces, united in their shared interest to

suppress or control history that doesn’t align with their preferred version of

events.

This suppression is not limited to South and Central America. In North

America, allegedly similar forces have worked to hide inconvenient truths.

There are persistent theories about institutions like the Smithsonian actively

suppressing evidence that challenges mainstream narratives. Researchers like

Graham Hancock and Brien Foerster—though not LDS—have spent their entire

careers exposing the hidden histories of ancient civilizations, much of which

aligns with the descriptions in the Book of Mormon.

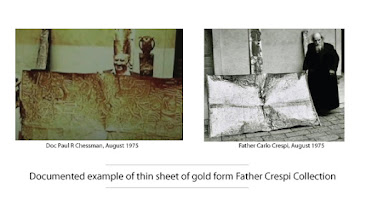

Take, for example, the gold in the Father Crespi collection.

A significant portion of the collection was composed of intricately worked gold

artifacts. Critics dismiss these items as forgeries, claiming they were created

by local natives to extract money from Father Crespi. The rebuttal to this

theory often hinges on a single claim: that in the 1920s–1950s, gold was of

little value to indigenous peoples. This argument is so absurd it collapses

under even the slightest scrutiny.

Consider the time, effort, and expertise required to gather

gold and process it. Some of the projects processed into sheets as thin as

tinfoil, with edges so precise they resemble the work of a modern machine. Some

of these sheets were 36 inches tall and over 50+ inches long—an astonishing

feat of craftsmanship. And the artistry? I hold a BFA in Graphic Design, and

while I’m no master artisan, I have studied great works and know enough to recognize the skill in these

pieces. These weren’t crude imitations but the work of master artisans, people

who had honed their craft over years, if not decades.

And here’s the kicker: many of these artifacts are adorned

with artwork unmistakably almost direct copy’s of Assyrian designs. Let me

repeat that—Assyrian designs. To believe the critics, you’d have to accept that

Ecuadorian natives not only mastered the skills to process and shape gold into

intricate sheets, plates, and statues, but also studied ancient Assyrian art

styles—without the internet, mind you—and flawlessly replicated them. All of

this, just to get a few coins from a kindly priest? The idea is laughable.

This brings me to the Spanish chroniclers. Among my father’s

notes, I found this account from one of the first chroniclers to enter Cusco,

Peru in the year 1533:

“The wonderfully carved granite walls of the temple were

covered with more than 700 sheets of pure gold, weighing around 4.5 pounds

each.”

The word “sheets” immediately caught my attention. Sheets of

gold, weighing approximately 4.5 pounds each. Now compare that to a story from

the 1975 Church-sponsored expedition to Ecuador. In a personal account, J.

Golden Barton described the moment when a large piece of gold sheet metal,

hammered and inscribed with intricate designs, was presented to inspect, touch and hold:

“They reappeared with a large piece of metal that had been

molded and hammered into a long sheet. It appeared to be gold. The metal was

inscribed with curious forms of artwork. I asked our good-natured leader to

pose for a photo holding the plaque. Now Paul was not one to do a lot of

clowning, but I treasure this picture.”

Later, when asked about its origins, Barton recounted that

Father Crespi had inquired about the sheet’s source. The native who brought it

replied that it had adorned the walls of a temple deep in Ecuador jungle—pulled

from its place and brought to Crespi as a relic of a lost time.

Do you see the pattern? The Spanish chroniclers described

sheets of gold in the temples of Cusco, sheets that disappeared with the

arrival of the conquistadors. Centuries later, similar sheets of gold, appeared

in Father Crespi’s collection. Are these coincidences, or are they fragments of

a larger story—one that ties the ancient civilizations of the Americas to their

Old World roots, just as the Book of Mormon describes?

The Father Crespi collection stands as both a witness and a warning. It tells us that there is more to the history of the Americas than we’ve been told, but it also reminds us how easily that history can be stolen, hidden, or destroyed. For those willing to dig deeper, the truth is there, waiting to be uncovered... If uncovered, will it ever see the light of day?