The black line suggests the gradual

curvature of the shoreline over a long distance. Unless one could see both

shores at the same time, they would not even suspect that there was a narrow

point in the middle

Consider how far a person can see along a straight line, such as a coastline while standing on the beach. Can one perceive a gradual curve as anything more than simply a curving or rounding piece of land at sea’s edge? Does anything that moves so gradually as this shoreline suggest anything other than a simple shoreline that gradually curves over a great distance?

As an example, the distance from

Veracruz, Mexico to Champoton on the Yucatan Peninsula, is 370 miles—about the

same distance as from Logan in northern Utah to St. George, in southern Utah.

Just exactly what curvature could you see in that distance?

As Sorenson says, “The only isthmus—and hence the only narrow neck of land—in geographical Mesoamerica is the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.” But what if you were not looking for a narrow neck of land? What if in Nephite times you were simply walking that distance along the shore—say, walking from Logan, Utah, to St. George, Utah, and deducing along the way that a shoreline was a gradual curve.

Could you even tell that?

Do you get the picture? There is simply no way that anyone could know that this was a narrowing of the land. And if you walked along the opposite southern shore of Mesoamerica, say from Santa Maria in Guatemala to Puerto Angel in Oaxaca, Mexico, a distance of about 370 miles (as the crow flies), what could you tell?

Nothing!

There are no mountains on the northern side of the Isthmus and the Sierra Madre to the south breaks down at this point into a broad, plateau-like ridge, whose elevation at the highest point is 735 feet, thus, there is no point in all of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec that is high enough from which a person in Nephite times could have seen both shores. Nor is there anywhere between the two Gulfs when crossing through the Chivela Pass or the swampy jungle beyond that would elevate a person to see the distant shore.

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec is a broad, plateau-like ridge that separates the Bay of Campeche (located in the Gulf of Mexico) in the north from the Gulf of Tehuantepec (part of the South Pacific Ocean) on the south. The southeastern parts of the Mexican states of Veracruz and Oaxaca occupy territory in the isthmus, while the Mexican states of Chiapas and Tabasco lie to its east. The Isthmus of Tehuantepec lies just to the west of the Yucatan Peninsula, where many consider Central America to be geographically separated from North

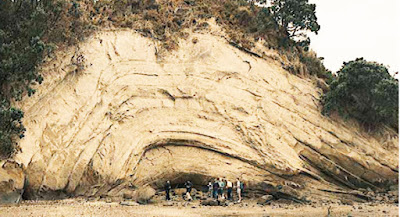

Along the coastal Gulf of Tehuantepec

that borders the Pacific Ocean. Top: Looking north along the shore line;

Bottom: Looking south along the shoreline

The Bay of Compeche shoreline off the

Gulf of Mexico. Top: Looking north; Middle: Looking south; Bottom: Along the

Gulf of Mexico at Tehuantepec

The point, and a very obvious one at that, is simply that it would have been impossible for Nephites, if they were living in Mesoamerica to have known that the Isthmus of Tehuantepec—which we can identify as an isthmus today only because of aerial photography, satellite imagery and NASA space shots—was in fact an isthmus, or even little more than a slight narrowing of the land—or, more likely, that there was a slight change in the shoreline. There would have been nothing whatsoever to lead them to think in terms of a “small” or “narrow” neck of land with the technology they had in their day.

Walking that land, viewing it form seashore views, even walking across it, would not have suggested in the slightest way that it was a narrow or small neck of land as Mormon writes. Obviously, without a vantage point where the land can be seen in its entirety, could anyone know that it was an isthmus. Even so, like today, there is no way anyone would look at that and say, oh, that is a “narrow neck of land,” for it does not give that impression from any view whatever, even from views unknown to the Nephites.

Thus, Sorenson accurately says, “The only isthmus—and hence the only narrow neck of land—in geographical Mesoamerica is the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.” It may be and may have been the only area. But in 600 B.C. or in Nephite times, there is no way anyone would have known, if they lived in that area, that there was an isthmus in Mesoamerica. Even today, it is a stretch to consider Tehuantepec an isthmus, even though it is so labeled on maps.

Consider the difference between what is

seen, a gradual indentation of the land, from the 1828 definition of

“isthmus”—“A neck

or narrow slip of land by which two continents are connected, or by which a

peninsula is united to the mainland…the word is applied to land of considerable

extent, between seas; as the isthmus

of Darien, which connects North and South America, and the isthmus between the Euxine and Caspian

seas“

What perspective would a person have to have to consider that kind of distance to equate to Mormon’s “small” or “narrow” description? Certainly not a perspective that the scriptural record is the guide and answer to things pertaining to the Land of Promise.

(See the

next post, “A Matter of Perspective – Part II,” for the rest of Allen’s

comments about the narrow neck and Sorenson’s views on the subject)