Southeast view of wet Stansbury

over central Skull Valley from Cedar Mountains Wilderness in the Cedar

Mountains

He then reminds us that “domestic animals were wiped out by Noah's flood and only brought back north of the narrow neck by the Jaredites. Chile would be too far south of the land north for any such domestic animals to have traveled to be available for Lehi's party. So there is no logical source of those domestic animals of the Jaredites to be south of the Atacama Desert around La Serena, Chile at the date of Lehi's landing.”

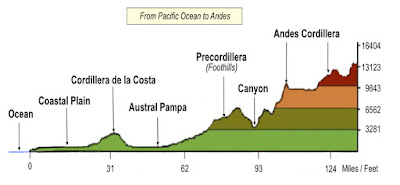

Again, Hender seems to lack a knowledge of the historical record of this area, and the topical terrain over which movement was made north to south from Peru to Chile as well as in the opposite direction. First, as has been mentioned earlier, most scientists who study the Atacama agree that about 1000 BC and long before that, the area was very different with far more rain and much more conducive to life. When the Jaredite animals came through the narrow neck of land, it would have been somewhere in the 1500s BC (See Jaredite Chronology in Who Really Settled Mesoamerica, Ch 12, p146), thus providing at least 500 years for some of these animals to drift southward through this area and to central Chile. On the other hand, the route that Nephi likely took northward from La Serena, would not have been along the coast and through the Atacama, but inland, close to what is now the Argentine border.

Map Nephi’s route

northward, through the foothills along the Andes onto the Altiplano, through

the La Raya Pass and to the Cuzco Valley. It would also have been an open

pathway for Jaredite animals into central Chile

It should also be kept in mind that foraging animals can end up just about anywhere, usually where people do not and would not go. Rounding up steers in wilderness areas should teach anyone that animals can be in the weirdest places and far distances from where they would be expected. To show this, in Texas, a small group of what are now called Longhorns, were introduced into Texas in the late 1600s—within 150 years or so, they roamed throughout more than 268,000-square miles of the state and beyond. This means these cattle spread over an area 790 miles long and 660 miles wide (Mary O. Parker, Explore Texas, Texas University Press, College Station, 2016). It should also be noted that western and northwestern Texas are mostly desert, and central Texas is part of the Great Plains, along with Caprock Escarpments, rolling plains, hills, high plains, with rugged mountains in the south.

Feral animals are typically hardy and fully capable of existing in the wild. Finding animals in central Chile would not have been surprising after 500 years—besides, it was a plan of the Lord and no doubt He had a hand in carrying it out.

Hender goes on to write: “Yet the Book of Mormon states that the land at the site of Lehi's landing was a bounteous land. When Lehi's party first landed they planted well needed crops and the land brought forth such abundantly. Logically this is not the arid Chilean site.”

Huge fields of grapes

growing in the bounteous land of La Serena and adjacent Elqui Valley where

crops grow in abundance throughout the year

The Mediterranean climate type, as we have mentioned many times, only occurs in five regions of the world: 1) the Mediterranean Basin and adjacent Atlantic Iberia, Morocco, and Canary Islands; 2) the southwestern tip of South Africa; 3) southwestern and south-central Australia; Central and Southern California; and central Chile around 30º South Latitude. They all share four key climatic characteristics: rainfall concentrated in the winter half-year (the most important factor), dry (and usually hot) summers, moderate winters (frosts are uncommon), and the regular, reliable alternation of the warm, dry summer with the cooler, rainier winter seasons.

The stable atmospheric high-pressure belts that sit at 30° N and 30° S latitudes are displaced equatorward in winter, allowing the westerlies to deliver moisture-laden storms. With the exception of Australia, fog is frequently present, and, with the exception of Chile, the vegetation is adapted to fire. Occupying only about two percent of the earth’s land surface, but with twenty percent of the world’s vascular plants, the Mediterranean flora is extremely diverse, and the vegetation is primarily open sclerophyll woodland, shrubland, and scrub. Chile’s Mediterranean-climate region includes an estimated 1,800-2,400 species and has among the highest rates of endemism in South America.

In Chile, this Mediterranean climate zone is between 29° S and 36° S latitudes, from La Serena to Valparaiso, with annual rainfalls averaging 11.8 to 31.5 inches. In Chile, the shrubland vegetation is known as matorral and, in many ways, is so similar to the analogous California chaparral that entire books have been written on the subject.

Differing from California’s chaparral is the occasional presence of a palm, arborescent bromeliads, and columnar cacti. The herbaceous cover is also greater in matorral than in chaparral and is mostly composed of perennials, but is relatively small, extending up to about 4,921 feet elevation, giving way higher up to montane matorral and alpine vegetation.

Top: North-South Central

Valley running along the east end of the Elqui Valley. Obviously this is not within the Atacama Desert, but part of a pathway up the center of the Chilean-Argentine lands toward the Altiplano in Peru and Bolivia

The Elqui River Basin covers an area of 5,993 square miles between the Andes and the coast, a width of about 120 miles, between 28º and 33º South Latitude, giving the area a longitudinal profile with strong inclination and narrow alluvial planes. Along the valley bottoms, the Elqui River originates downstream from the union of the Turbio and Claro rivers, and flows through La Serena and to Coquimbo Bay, where it empties into the Pacific Ocean. This Coquimbo Region with its transverse valleys is called the “Green North,” meaning a green area in northern Chile and known for its agricultural and mining importance especially gold, copper and iron. and is fed by the Elqui, Choapa and Limarí Rivers in the western marine terraces and middle mountains—an area significantly distinct from the rest of the arid and semiarid landscape that surrounds them (H. Bodini and F. Araya, Global Geographic Vision: The Region of Coquimbo, Center for Regional Studies, University of La Serena, Chile, 1998).

(See the next post, “Is the Chilean Landing Site Really a Myth? Part II,” for more regarding Dan R. Hender’s article on his website about the Chilean landing of Lehi is just a myth)