Continuing from the previous post regarding information

on the Rongorongo writing of Easter Island, claimed by its first inhabitants to

have been brought from the mainland to the east (South America), the script’s interpretation and

historical memory of the first inhabitants of the island, which at one time,

supported a relatively advanced and complex civilization.

While the earliest settlers of Easter Island

possessed both the Rongorongo tablets, and the ability to read and write the

language, in 1862, Peruvian slave ships captured nearly the entire population

of Easter Island. The remaining population does not seem to have been literate,

and knowledge of how to read the scripts was lost. While all such historic or legends

were handed down orally through the centuries, there is no way of verifying

this history. Published literature suggests the island was settled around

300–400 A.D., about the time of the arrival of the earliest settlers in Hawaii.

There is considerable debate among scientists about these dates and numerous

others, partly based on radio-carbon dating of woods and ashes that are

“believed” to have been old.

As for the ancient script, it is said by Easter

Islanders that only the master scribes engraved on wood, the apprentices

used banana leaves. It is claimed by some experts that rongo-rongo writing

notes that some experts consider that the writing was originally only on the banana leaves and that the Rongorongo boards were designed to look like banana leaves, even including the

ridges between the lines of writing which correspond to the veins on the banana

leaf.

Also of

interest is the tradition that the early Incas and ancient Peruvians had not

always been without writing-that they used to write codices like the Mayans

did, but on banana leaves, and that during times of war and famine all of the

old codices had been burnt up. This is scoffed at by experts saying there could

have been no banana leaves available then; however, Thor Heyerdahl points out

that Archaeologists had legitimately reported items found in Peruvian graves

wrapped in banana-leaves.

Evidently

banana leaves are preserved better in the Peruvian climate than would have

otherwise seemed likely, and adds to the old historical memory claims that the

Rongorongo writing came from the mainland to the east, that is, South America.

It might

be of interest to know, though today frowned upon, that in 1892 the Australian

pediatrician Alan Carroll published a fanciful translation, based on the idea

that the texts were written by an extinct “Long-Ear” population of Easter

Island in a diverse mixture of Quechua and other languages of Peru and

Mesoamerica. Perhaps due to the cost of casting special type for Rongorongo, no

method, analysis, or sound values of the individual glyphs were ever published.

Carroll continued to publish short communications in Science of Man, the

journal of the (Royal) Anthropological Society of Australasia until 1908.

When

the wooden tablets of writing were first discovered, by Eugène

Eyraud in 1864, he wrote: “In every

hut one finds wooden tablets or sticks covered in several sorts of hieroglyphic

characters: They are depictions of animals unknown on the island, which the

natives draw with sharp stones. Each figure has its own name; but the scant

attention they pay to these tablets leads me to think that these characters,

remnants of some primitive writing, are now for them a habitual practice which

they keep without seeking its meaning.”

Unfortunately,

to-date, according to Steven Fischer, the topic of the texts is unknown;

various investigators have speculated they cover genealogy, navigation,

astronomy, or agriculture (Steven Roger Fischer, RongoRongo, the Easter

Island Script: History, Traditions, Texts, Oxford University Press Oxford

and N.Y, 1997). Even so, Fischer has claimed some partial interpretations, but

other linguists disagree. So far, there is no agreement on the interpretation,

meaning or content of the writing.

In 1935, Steven Chauvet said: “The Bishop questioned the

Rapanui wise man, Ouroupano Hinapote, the son of the wise man Tekaki [who said

that] he, himself, had begun the requisite studies and knew how to carve the

characters with a small shark's tooth. He said that there was nobody left on

the island who knew how to read the characters since the Peruvians had brought

about the deaths of all the wise men and, thus, the pieces of wood were no

longer of any interest to the natives who burned them as firewood or wound

their fishing lines around them.” The French explorer, philologist and ethnographer,

Alphonse L. Pinart also saw some in 1877, but he was able to acquire only a

single set, because the natives were using them as reels for their fishing

lines” (The Pinart Collection at the Bancroft Library of the University of

California at Berkeley).

Today, only 26 examples of Rongorongo

text remain (with 3 disputed), each with letter codes inscribed on wooden

objects, containing between 2 and 2320 simple and compound glyphs, with over 15,000

in all. Two of the tablets, “C”

and “S,” have a documented

pre-missionary provenance, though others may be as old or older.

Unfortunately, this disappearance of the

written tablets has been identified and placed at the feet of the early

Catholic Church on Easter Island. Because of their sacred nature to the early

inhabitants of the island, the natives hid them from the European immigrants,

presumably because the missionaries considered the ceremonial documents as

idolatrous objects. The natives repeatedly asserted that the missionaries had

prohibited them from reading the tablets, and even had induced them to burn

these objects as devil's work. Of this, the Swede De Greno, who arrived about

1870 at Easter island, said:

“...soon after the Catholic Mission was

established on the Island, the missionaries persuaded many of the people to

consume by fire all the blocks (tablets) in their possession, telling them that

they were but heathen records and that the possession of them would have a

tendency to attach them to their heathenism and prevent their thorough

conversion to the new religion and the consequent saving of their souls..”

Also Katherine Pease Routledge, the renowned

English Archaeologist and Anthropologist, and also explorer of Easter island,

was told during the Mana Expedition to Rapa Nui in 1914 by a native that he

possessed a great number of tablets, all of which he had thrown away on the

advice of the missionaries, and afterwards another man had built a boat of them

(Katherine

Routledge: The Mystery of Easter Island, Cosmo Classics, New York, 2005;

Ed. Tregear and S. Percy Smith, Joint Hon, Secretaries, and Treasurers, and

Editors of Journal of the Polynesian

Solciety, No 1 Vol 1, April 15, 1892, University of Auckland).

Thomas

S. Barthel, Professor of Ethnology at the University of Tübingen in

Germany, which dates from 1477, was active in the mid-twentieth century

deciphering the Maya script, the hieroglyphic writing system of the pre-Columbian

Maya, and an influential researcher in the Mayan civilization, also spent time

as a guest researcher with the Institute for Easter Island Studies at the

University of Chile. It is his work on the Rongorongo written language claimed

to have been brought to the island by ancient settlers from Peru in their

historical memory of their history, that tells us about the ancient language. In order

to document Rongorongo, Barthel visited most of the museums which housed the

tablets, of which he made pencil rubbings. With this data he compiled the first

corpus of the script, which he published as Grundlagen zur Entzifferung der

Osterinselschrift (Bases for the Decipherment of the Easter Island Script),

Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Hamburg, 1958.

(See the next post, “Writing in South America –

Part III,” for information on the Rongorongo script and its interpretation and

the historical memory of the first inhabitants of the island)

Wednesday, January 31, 2018

Tuesday, January 30, 2018

Writing in South America – Part I

Easter Island (known as Rapa Nui in

Polynesian) covers roughly 64 square miles in the South Pacific Ocean, and is

located some 2,300 miles from Chile’s west coast and 2,500 miles east of

Tahiti. Its earliest inhabitants are believed by anthropologists to have

arrived in an organized party of emigrants around 300-400 A.D.

Tradition holds that the first king of Rapa Nui was Hoto-Matua, a ruler from Polynesia whose ship traveled thousands of miles before landing at Anakena, one of the few sandy beaches on the island’s rocky coast. The problem with that is simply that the winds and currents of the eastern South Pacific do not move in that direction from western Polynesia to Easter Island.

The island sits in the middle of an

open ocean, thousands of miles from the nearest neighboring island—Pitcairn Island is 1,289 miles to the east, or the mainland’s

closest point in central Chile near Concepcion 2,182 miles away, and is part of

the watercourse within the South Pacific Gyre. The island is 4,300 miles south

of Hawaii, and 3,700 miles north of the Antarctic.

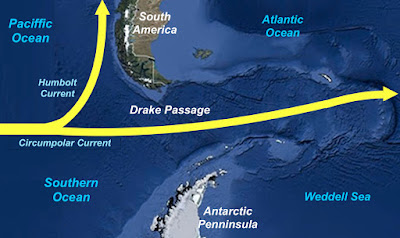

Here, the main current flows west to

east far south of Easter Island within the range of what is now called the

Southern Ocean, which passes across the Pacific just north of Antarctica in a

clockwise circular route to split at South America, with the lower portion

flowing through the Drake Passage from the Pacific into the Atlantic, and the

upper portion striking the South American continental shelf and bending upward,

along the west coast of Chile in what is also called the Humboldt (Peruvian)

Current until it strikes the Peruvian Bulge and is driven outward and

eventually swings into the northern arm of the South Pacific Gyre, flowing

westward back across the Pacific toward Indonesia and Australia, where it

eventually is driven southward to pick up the eastward flowing Southern Ocean once

again.

Rapa Nui (Spanish: Isla de Pascua), was christened Paaseiland, or Easter Island, by Dutch explorers in honor of the day of their arrival in 1722. It was annexed by Chile in the late 19th century and now maintains an economy based largely on tourism.

Easter Island’s most dramatic claim

to fame is an array of almost 900 giant stone figures that date back many

centuries. The statues reveal their creators to be master craftsmen and

engineers, and are distinctive among other stone sculptures found in Polynesian

cultures, and particularly those found in ancient Peru. There has been much speculation about the exact purpose of the

statues, the role they played in the ancient civilization of Easter Island and

the way they may have been constructed and transported.

According to Andrew Lawler, “Polynesians from Easter Island and natives of South America met and mingled long before Europeans voyaged the Pacific, according to a new genetic study of living Easter Islanders” (Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, New York, Oct 23, 2014).

Where the early settlers of Easter island came

from has long been a controversy among anthropologists, relying merely on

speculation and a total misunderstanding of winds and currents of the eastern

Pacific. However, now there is scientific evidence that suggests these people

originally came from South America, though the idea is not well received among

mainstream “scientists” who still want to claim man came over a Bering Sea Land Bridge from

Siberia to Alaska and down the Western Hemisphere to South America. They simply

cannot the face the fact that ancient man could have built ships to sail into the

Pacific Ocean and reached Easter Island from South America.

In a recent issue of Current Biology (J. Victor Moreno-Mayar, et al, “Genome-wide Ancestry Patterns in Rapanui Suggest Pre-European Admixture with Native Americans,” Vol.24, Iss.21, November 2014, pp2518-2525), researchers argue that the genes point to contact between Native Americans and Easter Islanders three centuries after Polynesians settled the island of Rapa Nui, famous for its massive stone statues. Although circumstantial evidence had hinted at such contact, this is the first direct human genetic evidence that has been found for it.”

These researchers genotyped and analyzed 650,000 markers for 27 living native Rapa Nui islanders, dating to 19-23 generations ago, in which the team found dashes of European and Native American genetic patterns. The European genetic material made up 16% of the genomes; it was relatively intact and was unevenly spread among the Rapa Nui population, suggesting that genetic recombination, which breaks up segments of DNA, has not been at work for long.

Native American DNA accounted for about 8% of the genomes. Islanders enslaved by Europeans in the 19th century and sent to work in South America could have carried some Native American genes back home, but this genetic legacy appeared much older. The segments were more broken and widely scattered, suggesting a much earlier encounter—as early as 1280 A.D.

This had always raised the question, did Polynesians land on South American beaches, or did Native Americans sail into the Pacific to reach Rapa Nui? “Our studies strongly suggest that Native Americans most probably arrived [on Rapa Nui] shortly after the Polynesians,” says team member Erik Thorsby, an immunologist at the University of Oslo.

His beliefs, which could support the controversial theory posited by Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl more than a half-century ago, that Native Americans had the skills to move west across the Pacific from South America.

On the other hand, native Americans could have landed on Rapa Nui initially many years earlier, with others coming much later, which is more consistent with the record of the native Easter Islanders whose own historical memory claims dating to when Europeans first discovered them. Also in support of this is the famed Sweet Potato, which was domesticated in the Andean highlands, and researchers recently determined that the crop spread west across Polynesia long before the Europeans arrived. Another hint of trans-Pacific exchange comes from chicken bones—unknown in the Americas before 1500 A.D.—excavated on a Chilean beach, which some believe predate Christopher Columbus.

Easter Island, one of the youngest inhabited territories in the Pacific, as well as one of the most isolated, was first recorded by European contact on 5 April (Easter Sunday) 1722, when Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen visited for a week and estimated there were 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants on the island. Later European visitors recorded the local oral traditions about the original settlers.

In these traditions, Easter Islanders claimed they arrived on the island in one or two ships, with one named Hotu Matu'a, the legendary first settler of Rapa Nui, who is said to have brought 67 tablets from his “land to the east” homeland [South America], proclaimed, or so we are told, that decipherment of a small fraction of the Rongorongo tablets would be attempted by other, in this sense foreign or alien, great ma'ori (skilled or old ones), that these attempts would fail, and that the vast majority of them would perish.

(See the next post, “Writing in South America – Part II,” for information on the Rongorongo script and its interpretation and the historical memory of the first inhabitants of the island)

Tradition holds that the first king of Rapa Nui was Hoto-Matua, a ruler from Polynesia whose ship traveled thousands of miles before landing at Anakena, one of the few sandy beaches on the island’s rocky coast. The problem with that is simply that the winds and currents of the eastern South Pacific do not move in that direction from western Polynesia to Easter Island.

The overall South Pacific Gyre that flows counter-clockwise across the

South Pacific (red arrow); Note the (dotted lines) fall out currents of the

gyre as it circles around toward its movement north—these curve westward down

into the center of the gyre into Polynesia, working against Polynesians moving

eastward across the Pacific, and flow from South America toward Easter Island

The

Circumpolar Current, called the West Wind Drift, driven by the Prevailing

Westerly Winds, flows all around the globe, unimpeded in the southern waters becasue it is

free of land masses

Rapa Nui (Spanish: Isla de Pascua), was christened Paaseiland, or Easter Island, by Dutch explorers in honor of the day of their arrival in 1722. It was annexed by Chile in the late 19th century and now maintains an economy based largely on tourism.

Moai statues of monolithic human figures carved anciently by the Rapa

Nui people on Easter Island. The tallest Moai, called Paro, was 33-feet tall

and weighed 82 tons. By the latter part of the 19th century, all had

fallen and these, facing inland at Ahu Tongariki, were restored by Chilean

archaeologist Claudio Cristino in the 1990s

According to Andrew Lawler, “Polynesians from Easter Island and natives of South America met and mingled long before Europeans voyaged the Pacific, according to a new genetic study of living Easter Islanders” (Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, New York, Oct 23, 2014).

Signs of Rapa Nui's volcanic origins

In a recent issue of Current Biology (J. Victor Moreno-Mayar, et al, “Genome-wide Ancestry Patterns in Rapanui Suggest Pre-European Admixture with Native Americans,” Vol.24, Iss.21, November 2014, pp2518-2525), researchers argue that the genes point to contact between Native Americans and Easter Islanders three centuries after Polynesians settled the island of Rapa Nui, famous for its massive stone statues. Although circumstantial evidence had hinted at such contact, this is the first direct human genetic evidence that has been found for it.”

These researchers genotyped and analyzed 650,000 markers for 27 living native Rapa Nui islanders, dating to 19-23 generations ago, in which the team found dashes of European and Native American genetic patterns. The European genetic material made up 16% of the genomes; it was relatively intact and was unevenly spread among the Rapa Nui population, suggesting that genetic recombination, which breaks up segments of DNA, has not been at work for long.

Native American DNA accounted for about 8% of the genomes. Islanders enslaved by Europeans in the 19th century and sent to work in South America could have carried some Native American genes back home, but this genetic legacy appeared much older. The segments were more broken and widely scattered, suggesting a much earlier encounter—as early as 1280 A.D.

This had always raised the question, did Polynesians land on South American beaches, or did Native Americans sail into the Pacific to reach Rapa Nui? “Our studies strongly suggest that Native Americans most probably arrived [on Rapa Nui] shortly after the Polynesians,” says team member Erik Thorsby, an immunologist at the University of Oslo.

His beliefs, which could support the controversial theory posited by Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl more than a half-century ago, that Native Americans had the skills to move west across the Pacific from South America.

On the other hand, native Americans could have landed on Rapa Nui initially many years earlier, with others coming much later, which is more consistent with the record of the native Easter Islanders whose own historical memory claims dating to when Europeans first discovered them. Also in support of this is the famed Sweet Potato, which was domesticated in the Andean highlands, and researchers recently determined that the crop spread west across Polynesia long before the Europeans arrived. Another hint of trans-Pacific exchange comes from chicken bones—unknown in the Americas before 1500 A.D.—excavated on a Chilean beach, which some believe predate Christopher Columbus.

Easter Island, one of the youngest inhabited territories in the Pacific, as well as one of the most isolated, was first recorded by European contact on 5 April (Easter Sunday) 1722, when Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen visited for a week and estimated there were 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants on the island. Later European visitors recorded the local oral traditions about the original settlers.

In these traditions, Easter Islanders claimed they arrived on the island in one or two ships, with one named Hotu Matu'a, the legendary first settler of Rapa Nui, who is said to have brought 67 tablets from his “land to the east” homeland [South America], proclaimed, or so we are told, that decipherment of a small fraction of the Rongorongo tablets would be attempted by other, in this sense foreign or alien, great ma'ori (skilled or old ones), that these attempts would fail, and that the vast majority of them would perish.

(See the next post, “Writing in South America – Part II,” for information on the Rongorongo script and its interpretation and the historical memory of the first inhabitants of the island)

Monday, January 29, 2018

More Comments from Readers – Part V

Here are more comments that we have received from readers of

this website blog:

Comment #1: “What do you think of Richard Hauck’s four seas? To my knowledge he is the only one besides you who even considers there to be four seas” Grandy W.

Response: It was John

E. Clark, an avid Mesoamericanist who said, “Any geography that tries to

accommodate a north and south sea, I think, is doomed to fail,” probably because, as a Mesoamericanist, he

can find only two seas, or possibly three, if one includes the Caribbean, as

Hauck does, in his Mesoamerican model.

Yet, Mormon writes: “And it came to pass that they did multiply and spread, and did go forth from the land southward to the land northward, and did spread insomuch that they began to cover the face of the whole earth, from the sea south to the sea north, from the sea west to the sea east” (Helaman 3:8), showing us that there are, indeed, four seas, or at least there were four seas at the time the Nephites occupied the Land of Promise. Obviously, the “Land Northward” (mentioned 31 times) and the “Land Southward” (mentioned 15 times) are the major land masses or areas in which the main people groups of the Book of Mormon lived. Evidently, they were surrounded by seas—a literal fact according to Jacob (2 Nephi 10:20).

Since Mesoamerica has only two main seas, the Pacific and the Atlantic, with the Caribbean possibly being considered a third sea area to their land model, they do not have a fourth (or south) sea. Thus, one had to be created where no separate sea existed, and Hauck labeled it in as the northern section of the Pacific Ocean. However, what Hauck and so many people seem to misunderstand is the purpose of naming land or sea areas anciently by directional names.

As an example, if you were in the middle of Montana, where, having driven through there in the past, is almost void of people, places, or settlements, especially in the northeast of the State, say around the headwaters of the Missouri River at Haxby or Fort Pierce. In that huge void of land circled by Dryer Place, Zortman, Malta, Saco, Glasgow and Fort Pierce, there is an area about 4,000 square miles of emptiness, and if you include the area to the south of the Missouri River, you can add another 2,500 square miles, or about 6,500 square miles overall. Now consider yourself in the middle of that area on a hot, summer day, without water, asking someone to tell you where water holes could be found.

Now they tell you that there is a West Waterhole and a South Waterhole. Would you, in the most wild imagination of your mind place those two directional places in the manner that Hauck has placed these two directional Seas?

People, without other landmarks, did not think the way Hauck claims the Nephites would have had to in order to place Seas in the directions that he did. And certainly the ancient Hebrews did not do so. As a result, I would say Hauck’s idea is ridiculous. But even if he reversed the two seas (West and South), which would at least make more sense, it would still be giving two names to one sea without any reason for separation would be without merit.

I suppose it would be possible to name one “North Sea West” and “South Sea West,” but again, that is not the way the ancients used directional naming, especially not the Hebrews who would never have considered combining two directions in one name, since directions had specific meanings to the Hebrews, the “west” being where God was going (God is in the East and comes from there heading to the West), and “south” is where man dwells and departs (man comes from the South).

It might be of interest, though only to the extent of early opinion of the Book of Mormon that Orson Pratt considered there to be seas all around the Land of Promise. It was Orson Pratt who added verse numbers (for the first time) and footnotes from 1879 to 1907 (Royal Skousen, ed., The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT., 2009, p740).

In that edition, footnotes to Helaman 3:8 identified the lands southward and northward as South and North America, and the four seas as the Antarctic (called “the Atlantic, south of Cape Horn”), Arctic, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans: “And it came to pass that they did multiply and spread, and did go forth from the land southward [g, South America] to the land northward [h, North America], and did spread insomuch that they began to cover the face of the whole earth, from the sea south [Atlantic, south of Cape Horn] to the sea north [Arctic, north of North America], from the sea west [Pacific] to the sea east [Atlantic]” (The Book of Mormon, translated by Joseph Smith, Jun., Division into Chapters and Verses, with references by Orson Pratt, Sen., William Budge, Liverpool, 187; Salt Lake City: Bureau of Information, 1907, p434).

Again, that was Orson Pratt, not the Hebrew way of thinking. But it does show that early on there was seen four seas surrounding the Land of Promise, which is pretty much the only explanation for Haleman 3:8.

Comment #2: “Do you know what happened to the stone box that Joseph retrieved the Golden Plates from? Did anyone ever see it other than Joseph? This is something I've been curious about for some time and there appears to be a lot of dis-information on the web about it, from Martin Harris seeing it 3 times, Oliver Cowdrey seeing & describing it in detail, to the stones "sliding down the mountain" and then being carried off. This last one I find very unlikely. Anyway, if you could address these questions in upcoming blogs I would greatly appreciate it!” Bryce L.

Response: Joseph Smith said of the box: “Having removed the earth, I obtained a lever, which I got fixed under the edge of the stone, and with a little exertion raised it up. I looked in, and there indeed did I behold the plates, the Urim and Thummim, and the breastplate, as stated by the messenger. The box in which they lay was formed by laying stones together in some kind of cement. In the bottom of the box were laid two stones crossways of the box, and on these stones lay the plates and the other things with them” (The Sacred Record, The Testimony of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 1999, pp8–9).

Comment #1: “What do you think of Richard Hauck’s four seas? To my knowledge he is the only one besides you who even considers there to be four seas” Grandy W.

The implausibility of Hauck’s

identifications of the sea south and the sea west as two adjacent parts of the

Pacific Ocean that have nothing separating them is obvious

Yet, Mormon writes: “And it came to pass that they did multiply and spread, and did go forth from the land southward to the land northward, and did spread insomuch that they began to cover the face of the whole earth, from the sea south to the sea north, from the sea west to the sea east” (Helaman 3:8), showing us that there are, indeed, four seas, or at least there were four seas at the time the Nephites occupied the Land of Promise. Obviously, the “Land Northward” (mentioned 31 times) and the “Land Southward” (mentioned 15 times) are the major land masses or areas in which the main people groups of the Book of Mormon lived. Evidently, they were surrounded by seas—a literal fact according to Jacob (2 Nephi 10:20).

Since Mesoamerica has only two main seas, the Pacific and the Atlantic, with the Caribbean possibly being considered a third sea area to their land model, they do not have a fourth (or south) sea. Thus, one had to be created where no separate sea existed, and Hauck labeled it in as the northern section of the Pacific Ocean. However, what Hauck and so many people seem to misunderstand is the purpose of naming land or sea areas anciently by directional names.

As an example, if you were in the middle of Montana, where, having driven through there in the past, is almost void of people, places, or settlements, especially in the northeast of the State, say around the headwaters of the Missouri River at Haxby or Fort Pierce. In that huge void of land circled by Dryer Place, Zortman, Malta, Saco, Glasgow and Fort Pierce, there is an area about 4,000 square miles of emptiness, and if you include the area to the south of the Missouri River, you can add another 2,500 square miles, or about 6,500 square miles overall. Now consider yourself in the middle of that area on a hot, summer day, without water, asking someone to tell you where water holes could be found.

Now they tell you that there is a West Waterhole and a South Waterhole. Would you, in the most wild imagination of your mind place those two directional places in the manner that Hauck has placed these two directional Seas?

People, without other landmarks, did not think the way Hauck claims the Nephites would have had to in order to place Seas in the directions that he did. And certainly the ancient Hebrews did not do so. As a result, I would say Hauck’s idea is ridiculous. But even if he reversed the two seas (West and South), which would at least make more sense, it would still be giving two names to one sea without any reason for separation would be without merit.

I suppose it would be possible to name one “North Sea West” and “South Sea West,” but again, that is not the way the ancients used directional naming, especially not the Hebrews who would never have considered combining two directions in one name, since directions had specific meanings to the Hebrews, the “west” being where God was going (God is in the East and comes from there heading to the West), and “south” is where man dwells and departs (man comes from the South).

It might be of interest, though only to the extent of early opinion of the Book of Mormon that Orson Pratt considered there to be seas all around the Land of Promise. It was Orson Pratt who added verse numbers (for the first time) and footnotes from 1879 to 1907 (Royal Skousen, ed., The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT., 2009, p740).

In that edition, footnotes to Helaman 3:8 identified the lands southward and northward as South and North America, and the four seas as the Antarctic (called “the Atlantic, south of Cape Horn”), Arctic, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans: “And it came to pass that they did multiply and spread, and did go forth from the land southward [g, South America] to the land northward [h, North America], and did spread insomuch that they began to cover the face of the whole earth, from the sea south [Atlantic, south of Cape Horn] to the sea north [Arctic, north of North America], from the sea west [Pacific] to the sea east [Atlantic]” (The Book of Mormon, translated by Joseph Smith, Jun., Division into Chapters and Verses, with references by Orson Pratt, Sen., William Budge, Liverpool, 187; Salt Lake City: Bureau of Information, 1907, p434).

Again, that was Orson Pratt, not the Hebrew way of thinking. But it does show that early on there was seen four seas surrounding the Land of Promise, which is pretty much the only explanation for Haleman 3:8.

Comment #2: “Do you know what happened to the stone box that Joseph retrieved the Golden Plates from? Did anyone ever see it other than Joseph? This is something I've been curious about for some time and there appears to be a lot of dis-information on the web about it, from Martin Harris seeing it 3 times, Oliver Cowdrey seeing & describing it in detail, to the stones "sliding down the mountain" and then being carried off. This last one I find very unlikely. Anyway, if you could address these questions in upcoming blogs I would greatly appreciate it!” Bryce L.

Response: Joseph Smith said of the box: “Having removed the earth, I obtained a lever, which I got fixed under the edge of the stone, and with a little exertion raised it up. I looked in, and there indeed did I behold the plates, the Urim and Thummim, and the breastplate, as stated by the messenger. The box in which they lay was formed by laying stones together in some kind of cement. In the bottom of the box were laid two stones crossways of the box, and on these stones lay the plates and the other things with them” (The Sacred Record, The Testimony of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 1999, pp8–9).

The box was not

really a box, but side and bottom stones fitted together with a cement-type

substance that held the stones together and made the box water-tight. Being

large enough to hold the plates, Urim and Thummim and a breastplate, it would

seem the stone box alone would have weighed a considerable amount, and though I

do not know, it seems likely it remained where Joseph first found it—that is,

hidden from the world until the Lord wants it discovered. In

fact, there are no reliable first-hand accounts of what happened to the

stone box after Joseph removed the contents.

One account from a book published in 1893, writing about a series of interviews a Mormon writer named Edward Stevenson, who was acquainted with Joseph Smith, relates what he was told by an 'old man' living near the Hill Cumorah: “stated that he had seen some good-sized flat stones that had rolled down and lay near the bottom of the hill. This had occurred after the contents of the box had been removed and these stones were doubtless the ones that formerly composed the box. I felt a strong desire to see these ancient relics and told him I would be much pleased to have him inform me where they were to be found. He stated that they had long since been taken away” (Reminiscences of Joseph the Prophet, And the Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon by Elder Edward Stevenson, 1893 Salt Lake City, Utah).

Oliver Cowdery did not claim to have seen the box, only received a detail account of it from Joseph Smith, having joined the Church in 1829, two years after Joseph removed the plates, and one year before he actually visited the hill Cumorah for the first time.

Martin Harris claimed to have seen a stone box while treasure hunting on the hill Cumorah, but not the stone box that had held the plates. Porter Rockwell claims to have found a chest three feet square in the Cumorah hill, but not the stone box Joseph described.

David Whitmer claims to have seen the box, which he called a “casket” three times “at the Hill Cumorah and seen the casket that contained the tablets and seerstone. Eventually the casket has been washed down to the foot of the hill, but it was to be seen when he last visited the historic place” (Salt Lake Herald, 12 August 1875; reprinting from Chicago Times, 7 August 1875; cited in Ebbie L V Richardson, “David Whitmer: A Witness to the Divine Authenticity of the Book of Mormon,” M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1952, pp156-158; Also in Lyndon Cook (editor), David Whitmer Interviews: A Restoration Witness, Grandin Books, Orem UT, 1991, p7).

On the other hand, Joseph Smith never stated that he showed the stone box to anyone. Other than this, there isn’t much to comment upon.

One account from a book published in 1893, writing about a series of interviews a Mormon writer named Edward Stevenson, who was acquainted with Joseph Smith, relates what he was told by an 'old man' living near the Hill Cumorah: “stated that he had seen some good-sized flat stones that had rolled down and lay near the bottom of the hill. This had occurred after the contents of the box had been removed and these stones were doubtless the ones that formerly composed the box. I felt a strong desire to see these ancient relics and told him I would be much pleased to have him inform me where they were to be found. He stated that they had long since been taken away” (Reminiscences of Joseph the Prophet, And the Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon by Elder Edward Stevenson, 1893 Salt Lake City, Utah).

Oliver Cowdery did not claim to have seen the box, only received a detail account of it from Joseph Smith, having joined the Church in 1829, two years after Joseph removed the plates, and one year before he actually visited the hill Cumorah for the first time.

Martin Harris claimed to have seen a stone box while treasure hunting on the hill Cumorah, but not the stone box that had held the plates. Porter Rockwell claims to have found a chest three feet square in the Cumorah hill, but not the stone box Joseph described.

David Whitmer claims to have seen the box, which he called a “casket” three times “at the Hill Cumorah and seen the casket that contained the tablets and seerstone. Eventually the casket has been washed down to the foot of the hill, but it was to be seen when he last visited the historic place” (Salt Lake Herald, 12 August 1875; reprinting from Chicago Times, 7 August 1875; cited in Ebbie L V Richardson, “David Whitmer: A Witness to the Divine Authenticity of the Book of Mormon,” M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, 1952, pp156-158; Also in Lyndon Cook (editor), David Whitmer Interviews: A Restoration Witness, Grandin Books, Orem UT, 1991, p7).

On the other hand, Joseph Smith never stated that he showed the stone box to anyone. Other than this, there isn’t much to comment upon.

Sunday, January 28, 2018

More Comments from Readers – Part IV

Here are more comments that we have received from readers of

this website blog:

Comment #1: “It seems to me that Joseph Smith got the names he used in the Book of Mormon from the Bible” Catherine C.

Response: Really? Joseph Smith introduced nearly 200 new names which are not found in the Bible and which have long been the source of anti-Mormon attacks on the authenticity of the Book of Mormon, that is, until recently.

As an example, the name Sam, is a perfectly good Hebrew name, equivalent to Shem, one of Noah's sons (not necessarily short for Samuel). On the other hand, for quite some time, though, the name Alma was derided as a gaffe in the Book of Mormon, since "everyone knows" it is a female name in Latin and Spanish, not a Jewish man's name. Then a discovery in Israel apparently showed that it was a real Jewish man's name from roughly the time of Lehi. While this discovery ought to give the critics food for thought, it was ignored or rapidly dismissed, and more recently attacked by some critics having a minute knowledge of Hebrew. For example, one critic e-mailed the following question: "Why do pro-LDS apologists cite names such as 'Alma' as evidence? In Hebrew, vowels are omitted so any 'new discovery' is just a coincidence.”

Since Alma would be LM, the combination is endless; however, though critics tend to always dismiss any evidence as just coincidence, in this case, as with many others, there is little basis for the dismissal. The critic implies that all we have for the name Alma is two consonants that could just as easily be pronounced Elmo, Alum, Olemo, etc. But this is not the case, for the name in the ancient Jewish document is actually spelled with four letters, beginning with an aleph אלמה. The name appears in two forms that differ in the final letter, but "Alma" fits both.

For scholars of Hebrew, there is good evidence that the name should be "Alma," which is exactly how the non-LDS Israel scholar, Yigael Yadin (left), transliterated it. For details, see Paul Hoskisson, “What’s in a Name?”, Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1, 1998, pp72-73), which shows a color photograph (in the printed publication) of the document that has the name Alma twice. John Tvedtnes also discussed the name Alma in a well-received presentation to other non-LDS scholars, “Hebrew Names in the Book of Mormon,” where he noted that in addition to being found as a male name in one of the Bar Kochba documents, it is also found as a medieval place name in Eretz, Israel and as a personal male name from Ebla (Also see John Tvedtnes, John Gee, and Matthew Roper, “Book of Mormon Names Attested in Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions”).

Also Paul Hoskisson, following up on previous notes from Hugh Nibley (Hugh W. Nibley, The Prophetic Book of Mormon, Deseret Book, 1989, pp281–82; See also the original notice of the discovery in Yigael Yadin, Bar Kokhba, Random House, New York, 1971, p176), showed that the name Alma appears on a Jewish document of the early second century A.D., also found in Israel (Paul Y. Hoskisson, “Alma as a Hebrew Name,” JBMS 7/1, 1998, p72–73. See also the discussion in David K. Geilman, “5/6Hev 44 Bar Kokhba,” in Ancient Scrolls from the Dead Sea, ed. M. Gerald Bradford, Provo, Utah, FARMS, 1997, p39).

Comment #2: “I find it out of character for a missionary to be carrying a sword, and especially, as Ammon did, use it to cut off the arms of Lamanites harassing the king’s sheep. Can you imagine such a thing today?” Carlo S.

Response: We find in Alma 17 the story of Ammon. Remember, he was a Nephite traveling in Lamanite country, and according to Mormon’s words: “Having taken leave of their father, Mosiah, in the first year of the judges; having refused the kingdom which their father was desirous to confer upon them, and also this was the minds of the people; Nevertheless they departed out of the land of Zarahemla, and took their swords, and their spears, and their bows, and their arrows, and their slings; and this they did that they might provide food for themselves while in the wilderness. And thus they departed into the wilderness with their numbers which they had selected, to go up to the land of Nephi, to preach the word of God unto the Lamanites” (Mosiah 17:6-8).

Later, we find that every man that lifted his club to smite Ammon, he smote off their arms with his sword; for he did withstand their blows by smiting their arms with the edge of his sword, insomuch that they began to be astonished, and began to flee before him; yea, and they were not few in number; and he caused them to flee by the strength of his arm. Now six of them had fallen by the sling, but he slew none save it were their leader with his sword; and he smote off as many of their arms as were lifted against him, and they were not a few. And when he had driven them afar off, he returned and they watered their flocks” (Mosiah 17:37-39).

Let us not forget that even the Apostle Peter carried a

sword among the Savior’s close followers. If you lived in that day, a weapon

for protection and for obtaining your food would have been essential. In fact,

the Lord himself instructed his disciples to obtain swords, saying: “But now if you have a purse, take it, and also a bag; and if you don’t have a sword, sell your cloak and buy one” (Luke 22:37).

Comments #3: “In a book called ‘In Search of Cumorah,’ I find that the author makes a good point about there being buildings all around the area of the Jaredite last battles—which means Cumorah should have artifacts of numerous buildings from around the end of the Jaredite period. Surely some of those would have been found, or parts of them, if they were built in stone” Andy S.

Response: The author, David A. Palmer who, by the way, is a Mesoamericanist, is trying to make this point on p60 of his book, however, what he fails to point out is that at the point of his discussing these buildings (Ether 14:17) which Shiz destroys is not near Ramah—they are early in the battles that afterward went from where they took place around these cities to the east seashore (Ether 14:26), then to the valleys of Corohor and Shurr (Ether 14:28), then they separated while each side recovered from the battles (Ether 14:31). Another serious battle takes place at an undisclosed area, then they fled north to Ripliancum (15:8), and from there they fled southward to Ogath where Coriantumr pitched his tents near the hill Ramah (Ether 15:11). As you can see, they could have been near or many miles away from these buildings.

We cannot suggest any connection here between the area of Ramah and anything else that might have survived. Following these events they spent four years gathering together every Jaredite in the land to their two armies (Ether 15:12-15). And where Shiz and Coriantumr battled, was at least one day’s flight from Ramah/Cumorah (15:28). We simply have no confirmation in these events that the battle at Ramah was anywhere near populated areas, buildings, etc., and any suggestion that it was is simply speculative and not supported by the scriptural record.

Comment #5: “How can you expect me to believe the Book of Mormon when all the witnesses left the Church. Seems very suspicious to me!” Janice W.

Response: People leave the Church for various reasons, but in the case of the witnesses, none ever denied seeing the Plates who saw them or the work of the Book of Mormon who were involved in transcribing Joseph’s translation. Nor did all the witnesses leave the Church. Being a member in the early days of the Church was very difficult and fraught with pain, sacrifice, and heartache, not all of which came from external persecution. People frequently have personal problems with strong leaders like Joseph Smith, and those with natural human pride can be easily offended. The same happened with Christ, as you will recall: he said that many would be offended (Matt. 26:31), and John 6:61-66 reports that many of his disciples rejected him, apparently offended by some of his teachings. Now if an offended person still sticks to a story that adds credibility to someone he has rejected, isn't that pretty impressive? That's the case for Joseph Smith and the witnesses of the Book of Mormon. You can read their testimonies which they never changed.

Comment #1: “It seems to me that Joseph Smith got the names he used in the Book of Mormon from the Bible” Catherine C.

Response: Really? Joseph Smith introduced nearly 200 new names which are not found in the Bible and which have long been the source of anti-Mormon attacks on the authenticity of the Book of Mormon, that is, until recently.

As an example, the name Sam, is a perfectly good Hebrew name, equivalent to Shem, one of Noah's sons (not necessarily short for Samuel). On the other hand, for quite some time, though, the name Alma was derided as a gaffe in the Book of Mormon, since "everyone knows" it is a female name in Latin and Spanish, not a Jewish man's name. Then a discovery in Israel apparently showed that it was a real Jewish man's name from roughly the time of Lehi. While this discovery ought to give the critics food for thought, it was ignored or rapidly dismissed, and more recently attacked by some critics having a minute knowledge of Hebrew. For example, one critic e-mailed the following question: "Why do pro-LDS apologists cite names such as 'Alma' as evidence? In Hebrew, vowels are omitted so any 'new discovery' is just a coincidence.”

Since Alma would be LM, the combination is endless; however, though critics tend to always dismiss any evidence as just coincidence, in this case, as with many others, there is little basis for the dismissal. The critic implies that all we have for the name Alma is two consonants that could just as easily be pronounced Elmo, Alum, Olemo, etc. But this is not the case, for the name in the ancient Jewish document is actually spelled with four letters, beginning with an aleph אלמה. The name appears in two forms that differ in the final letter, but "Alma" fits both.

For scholars of Hebrew, there is good evidence that the name should be "Alma," which is exactly how the non-LDS Israel scholar, Yigael Yadin (left), transliterated it. For details, see Paul Hoskisson, “What’s in a Name?”, Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1, 1998, pp72-73), which shows a color photograph (in the printed publication) of the document that has the name Alma twice. John Tvedtnes also discussed the name Alma in a well-received presentation to other non-LDS scholars, “Hebrew Names in the Book of Mormon,” where he noted that in addition to being found as a male name in one of the Bar Kochba documents, it is also found as a medieval place name in Eretz, Israel and as a personal male name from Ebla (Also see John Tvedtnes, John Gee, and Matthew Roper, “Book of Mormon Names Attested in Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions”).

Also Paul Hoskisson, following up on previous notes from Hugh Nibley (Hugh W. Nibley, The Prophetic Book of Mormon, Deseret Book, 1989, pp281–82; See also the original notice of the discovery in Yigael Yadin, Bar Kokhba, Random House, New York, 1971, p176), showed that the name Alma appears on a Jewish document of the early second century A.D., also found in Israel (Paul Y. Hoskisson, “Alma as a Hebrew Name,” JBMS 7/1, 1998, p72–73. See also the discussion in David K. Geilman, “5/6Hev 44 Bar Kokhba,” in Ancient Scrolls from the Dead Sea, ed. M. Gerald Bradford, Provo, Utah, FARMS, 1997, p39).

Comment #2: “I find it out of character for a missionary to be carrying a sword, and especially, as Ammon did, use it to cut off the arms of Lamanites harassing the king’s sheep. Can you imagine such a thing today?” Carlo S.

Response: We find in Alma 17 the story of Ammon. Remember, he was a Nephite traveling in Lamanite country, and according to Mormon’s words: “Having taken leave of their father, Mosiah, in the first year of the judges; having refused the kingdom which their father was desirous to confer upon them, and also this was the minds of the people; Nevertheless they departed out of the land of Zarahemla, and took their swords, and their spears, and their bows, and their arrows, and their slings; and this they did that they might provide food for themselves while in the wilderness. And thus they departed into the wilderness with their numbers which they had selected, to go up to the land of Nephi, to preach the word of God unto the Lamanites” (Mosiah 17:6-8).

Later, we find that every man that lifted his club to smite Ammon, he smote off their arms with his sword; for he did withstand their blows by smiting their arms with the edge of his sword, insomuch that they began to be astonished, and began to flee before him; yea, and they were not few in number; and he caused them to flee by the strength of his arm. Now six of them had fallen by the sling, but he slew none save it were their leader with his sword; and he smote off as many of their arms as were lifted against him, and they were not a few. And when he had driven them afar off, he returned and they watered their flocks” (Mosiah 17:37-39).

The Apostle Peter in a famed painting by Peter Paul Rubens showing a

prominent sword in hand

Comments #3: “In a book called ‘In Search of Cumorah,’ I find that the author makes a good point about there being buildings all around the area of the Jaredite last battles—which means Cumorah should have artifacts of numerous buildings from around the end of the Jaredite period. Surely some of those would have been found, or parts of them, if they were built in stone” Andy S.

Response: The author, David A. Palmer who, by the way, is a Mesoamericanist, is trying to make this point on p60 of his book, however, what he fails to point out is that at the point of his discussing these buildings (Ether 14:17) which Shiz destroys is not near Ramah—they are early in the battles that afterward went from where they took place around these cities to the east seashore (Ether 14:26), then to the valleys of Corohor and Shurr (Ether 14:28), then they separated while each side recovered from the battles (Ether 14:31). Another serious battle takes place at an undisclosed area, then they fled north to Ripliancum (15:8), and from there they fled southward to Ogath where Coriantumr pitched his tents near the hill Ramah (Ether 15:11). As you can see, they could have been near or many miles away from these buildings.

We cannot suggest any connection here between the area of Ramah and anything else that might have survived. Following these events they spent four years gathering together every Jaredite in the land to their two armies (Ether 15:12-15). And where Shiz and Coriantumr battled, was at least one day’s flight from Ramah/Cumorah (15:28). We simply have no confirmation in these events that the battle at Ramah was anywhere near populated areas, buildings, etc., and any suggestion that it was is simply speculative and not supported by the scriptural record.

Comment #5: “How can you expect me to believe the Book of Mormon when all the witnesses left the Church. Seems very suspicious to me!” Janice W.

Response: People leave the Church for various reasons, but in the case of the witnesses, none ever denied seeing the Plates who saw them or the work of the Book of Mormon who were involved in transcribing Joseph’s translation. Nor did all the witnesses leave the Church. Being a member in the early days of the Church was very difficult and fraught with pain, sacrifice, and heartache, not all of which came from external persecution. People frequently have personal problems with strong leaders like Joseph Smith, and those with natural human pride can be easily offended. The same happened with Christ, as you will recall: he said that many would be offended (Matt. 26:31), and John 6:61-66 reports that many of his disciples rejected him, apparently offended by some of his teachings. Now if an offended person still sticks to a story that adds credibility to someone he has rejected, isn't that pretty impressive? That's the case for Joseph Smith and the witnesses of the Book of Mormon. You can read their testimonies which they never changed.

Saturday, January 27, 2018

More Comments from Readers - Part III

More

comments and questions from our readers of this blog:

Comment #1: “Your Book of Mormon talks about the Nephites having a compass, but the use of the magnetic compass was unknown in 600 B.C.” Jan A.

Response: This is the type of problem we run into when people become critics over issues of history that they do not fully know, but trust to “general knowledge.” As an example, the function of magnetic hematite was well understood in both the Old and New Worlds before Lehi left Jerusalem.

Magnetite,

or lodestone, is, of course, naturally magnetic iron, and the word magnetite

comes from the name of a place in which it was mined in Asia Minor by at least

the seventh century B.C., many years before Lehi left Jerusalem, called Magnesia, in what is today Turkey.

In addition, China had such a compass before 200 B.C. in their “south-pointer” a spoon-shaped instrument in a cast bronze plate called a “heaven-plate” or “diviner’s board.” The original use of Ancient Chinese compasses was for maintaining harmony and prosperity with one’s environment in a philosophical system of harmonizing everyone with the surrounding environment, as well as for telling the future—it was one of the Five Arts of Chinese Metaphysics, classified as physiognomy, that is observation of appearances through formulas and calculations.

In ancient China, it was believed that if your home was placed in the right direction, then you would have a good life including good health and much wealth. Today, we know this practice as feng shui, which, as we know today, discusses architecture in metaphoric terms of "invisible forces" that bind the universe, earth, and humanity together, known as “qi.”

Besides, the use of a magnetic compass would have been known to God from the beginning and since it was He who made the compass and provide it for Lehi, one cannot say it was unknown at that time. The word, of course, would not have been known, but translation is based on purpose and meaning, not always on specific words.

Comment#3: “I think we should be careful to use any variation of the statement "the Book of Mormon doesn't mention them" as an argument against them. By the same token, we can't conclusively say that the east sea disappeared after 3rd Nephi simply because it is no longer mentioned. The most we can say is that the lack of mention is only supportive of the thesis, but it does not prove it. Let me give an example: the Book of Mormon makes no mention of any Lehites eating fish, it's completely silent on the matter. It does, however, mention other food and drink that they DID eat. Are we to then conclude that Lehites didn't eat fish because the Book of Mormon says nothing about it? I think most people would think that a ridiculous notion. Given the preponderance of "waters," "rivers," "fountains," and the "seashores" often mentioned, using our knowledge of human existence, and considering that there's probably not a single historical people anywhere in the americas who DIDN'T eat fish, it's probably safe to say they ate fish—even though the Book of Mormon doesn't explicitly say it. Just some thoughts” Wonder Boy.

Response: As we have written from time to time, any and all information regarding the geography of the Land of Promise is to some extent assumptive, since it was not written as a geographical work, nor even a history, and much is not covered. On the other hand, as we have also said, that when Mormon makes reference to the “Sea East” twenty-four times, with 20 of them in his brief abridgement of Alma, and often regarding the Lamanites and wars, one might think that when he says “the war began among them” (Mormon 1:10), he neither mentions the Sidon River nor the Sea East. While that is not conclusive, it certainly does not fit in with his typical writing on the subject.

As for your example of the fish, perhaps we ought to look at it in greater context to the writing of Mormon. As an example, if the scriptural record said the Nephites had eaten fish in 20 different references, then of a sudden said there was a drastic change in diet brought about by a cataclysmic event, then went on to say what they ate after that and did not mention fish, one might draw a rather conclusive, though assumptive, conclusion from this change in comment. If we are going to use examples, they need to be representative of the facts or the comparison.

As for the Sea East, there are other factors—It did exist, it is frequently mentioned, and there was an island, and the Nephites had built several cities along that coast, which was mentioned numerous times, as was the fact that the Lamanites attacked these cities from time to time when commencing a war, etc., but when they commenced a war (which turned out to launch the final battles of the nation) the Lamanites were doing so in the area they had done so in the past (near the Sidon), yet no mention of the cities, Sea East, coast, seashore, etc. I take that as very particular, though as you say, not fact. Still, we have suggested other ideas on no less of suggestive things, which fit the picture better than something else. After all, when it comes to the geography of the Land of Promise in the Book of Mormon, there are few concrete "facts"—mostly just ideas.

Comment #3: “How did the plates get from South America to upstate New York?” Carlisle J.

Response: We might just as well ask, when Nephi in 1 Nephi 11:1 sat pondering in his heart, he was caught away in the Spirit of the Lord, yea, into an exceedingly high mountain, which he never had before seen, and upon which he never had before set his foot—how did he get there? Or, we might ask, when Joseph and Oliver took the plates back to the Hill Cumorah in New York, the hill opened, and they walked into a cave, in which there was a large and spacious room. They laid the plates on a table, under which was a pile of plates as much as two feet high, and there were altogether in this room more plates than probably many wagon loads—since the hill in New York is a drumlin hill, that is a hill of glacial till where no cave could exist, where were they and how did they get there?

To ask how the Lord accomplishes

what he does is fruitless, or even how visions work. He labors in spheres far beyond our knowledge.

Transporting items from one place to another for the one who helped create the

Universe and formed the Earth, such questions are meaningless.

As a guess about the plates, it may he been that this was done after Moroni was finished writing. That is, he took the plates to New York from the Ecuadorian area. How this was done, is not known. After all, the Lord has the power to move objects, matter, etc., at His will. On the other hand, many years after the event, David Whitmer told Elder Joseph F. Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve about his wagon trip to Fayette with Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery. As they traveled across a section of prairie, they came upon a man walking along the road, carrying something that was obviously heavy in a knapsack on his back. Invited to ride, the man replied, “No, I am going to Cumorah.” Puzzled, David glanced at Joseph Smith inquiringly, but when he turned again, the man was gone. David demanded of Joseph: “‘What does it mean?’

Joseph informed him that the man was Moroni, and that the bundle on his back contained plates which Joseph had delivered to him before they departed from Harmony, Susquehanna County, and that he was taking them for safety, and would return them when he (Joseph) reached father Whitmer’s home.” (Andrew Jenson, ed., The Historical Record, vol. 6, May 1887, pp. 207–9.)

As we understand it, Moroni’s great mission after his translation (or resurrection) was to look after this Nation. He is its guardian angel, so to speak, and would be involved in just about everything righteous that takes place here. His moving the plates (wagon loads of plates) from Ecuador to New York would not be much of a deal for such a being—the Brother of Jared moved a mountain. On the other hand, we do not know and have not been told how he did that—the one thing that is certain, those plates were not originally buried in the Hill Cumorah in upstate New York. Having been through that land and seen and walked upon the hill—nothing about it could possibly match the description within the scriptural record about Mormon’s last battle.

Comment #1: “Your Book of Mormon talks about the Nephites having a compass, but the use of the magnetic compass was unknown in 600 B.C.” Jan A.

Response: This is the type of problem we run into when people become critics over issues of history that they do not fully know, but trust to “general knowledge.” As an example, the function of magnetic hematite was well understood in both the Old and New Worlds before Lehi left Jerusalem.

Magnesia, Asia Minor, where magnetic

iron was first discovered, and from whence the name Magnetic comes

In addition, China had such a compass before 200 B.C. in their “south-pointer” a spoon-shaped instrument in a cast bronze plate called a “heaven-plate” or “diviner’s board.” The original use of Ancient Chinese compasses was for maintaining harmony and prosperity with one’s environment in a philosophical system of harmonizing everyone with the surrounding environment, as well as for telling the future—it was one of the Five Arts of Chinese Metaphysics, classified as physiognomy, that is observation of appearances through formulas and calculations.

In ancient China, it was believed that if your home was placed in the right direction, then you would have a good life including good health and much wealth. Today, we know this practice as feng shui, which, as we know today, discusses architecture in metaphoric terms of "invisible forces" that bind the universe, earth, and humanity together, known as “qi.”

Besides, the use of a magnetic compass would have been known to God from the beginning and since it was He who made the compass and provide it for Lehi, one cannot say it was unknown at that time. The word, of course, would not have been known, but translation is based on purpose and meaning, not always on specific words.

Comment#3: “I think we should be careful to use any variation of the statement "the Book of Mormon doesn't mention them" as an argument against them. By the same token, we can't conclusively say that the east sea disappeared after 3rd Nephi simply because it is no longer mentioned. The most we can say is that the lack of mention is only supportive of the thesis, but it does not prove it. Let me give an example: the Book of Mormon makes no mention of any Lehites eating fish, it's completely silent on the matter. It does, however, mention other food and drink that they DID eat. Are we to then conclude that Lehites didn't eat fish because the Book of Mormon says nothing about it? I think most people would think that a ridiculous notion. Given the preponderance of "waters," "rivers," "fountains," and the "seashores" often mentioned, using our knowledge of human existence, and considering that there's probably not a single historical people anywhere in the americas who DIDN'T eat fish, it's probably safe to say they ate fish—even though the Book of Mormon doesn't explicitly say it. Just some thoughts” Wonder Boy.

Response: As we have written from time to time, any and all information regarding the geography of the Land of Promise is to some extent assumptive, since it was not written as a geographical work, nor even a history, and much is not covered. On the other hand, as we have also said, that when Mormon makes reference to the “Sea East” twenty-four times, with 20 of them in his brief abridgement of Alma, and often regarding the Lamanites and wars, one might think that when he says “the war began among them” (Mormon 1:10), he neither mentions the Sidon River nor the Sea East. While that is not conclusive, it certainly does not fit in with his typical writing on the subject.

As for your example of the fish, perhaps we ought to look at it in greater context to the writing of Mormon. As an example, if the scriptural record said the Nephites had eaten fish in 20 different references, then of a sudden said there was a drastic change in diet brought about by a cataclysmic event, then went on to say what they ate after that and did not mention fish, one might draw a rather conclusive, though assumptive, conclusion from this change in comment. If we are going to use examples, they need to be representative of the facts or the comparison.

As for the Sea East, there are other factors—It did exist, it is frequently mentioned, and there was an island, and the Nephites had built several cities along that coast, which was mentioned numerous times, as was the fact that the Lamanites attacked these cities from time to time when commencing a war, etc., but when they commenced a war (which turned out to launch the final battles of the nation) the Lamanites were doing so in the area they had done so in the past (near the Sidon), yet no mention of the cities, Sea East, coast, seashore, etc. I take that as very particular, though as you say, not fact. Still, we have suggested other ideas on no less of suggestive things, which fit the picture better than something else. After all, when it comes to the geography of the Land of Promise in the Book of Mormon, there are few concrete "facts"—mostly just ideas.

Comment #3: “How did the plates get from South America to upstate New York?” Carlisle J.

Response: We might just as well ask, when Nephi in 1 Nephi 11:1 sat pondering in his heart, he was caught away in the Spirit of the Lord, yea, into an exceedingly high mountain, which he never had before seen, and upon which he never had before set his foot—how did he get there? Or, we might ask, when Joseph and Oliver took the plates back to the Hill Cumorah in New York, the hill opened, and they walked into a cave, in which there was a large and spacious room. They laid the plates on a table, under which was a pile of plates as much as two feet high, and there were altogether in this room more plates than probably many wagon loads—since the hill in New York is a drumlin hill, that is a hill of glacial till where no cave could exist, where were they and how did they get there?

Typical Drumlin Hill

As a guess about the plates, it may he been that this was done after Moroni was finished writing. That is, he took the plates to New York from the Ecuadorian area. How this was done, is not known. After all, the Lord has the power to move objects, matter, etc., at His will. On the other hand, many years after the event, David Whitmer told Elder Joseph F. Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve about his wagon trip to Fayette with Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery. As they traveled across a section of prairie, they came upon a man walking along the road, carrying something that was obviously heavy in a knapsack on his back. Invited to ride, the man replied, “No, I am going to Cumorah.” Puzzled, David glanced at Joseph Smith inquiringly, but when he turned again, the man was gone. David demanded of Joseph: “‘What does it mean?’

Joseph informed him that the man was Moroni, and that the bundle on his back contained plates which Joseph had delivered to him before they departed from Harmony, Susquehanna County, and that he was taking them for safety, and would return them when he (Joseph) reached father Whitmer’s home.” (Andrew Jenson, ed., The Historical Record, vol. 6, May 1887, pp. 207–9.)

As we understand it, Moroni’s great mission after his translation (or resurrection) was to look after this Nation. He is its guardian angel, so to speak, and would be involved in just about everything righteous that takes place here. His moving the plates (wagon loads of plates) from Ecuador to New York would not be much of a deal for such a being—the Brother of Jared moved a mountain. On the other hand, we do not know and have not been told how he did that—the one thing that is certain, those plates were not originally buried in the Hill Cumorah in upstate New York. Having been through that land and seen and walked upon the hill—nothing about it could possibly match the description within the scriptural record about Mormon’s last battle.

Friday, January 26, 2018

More Comments from Readers Part II

Following are more comments and

questions from our readers: Comment #1 “I find it

hard to believe you can defend Joseph Smith for marrying 14 year olds and

brothers and sisters. How repulsive” Erma J.

Response: Indeed it would be if that was the case, but what

you claim are marriages were sealings, which are conducted today in every LDS

temple, i.e., sealing of a family together for time and eternity. As an

example, when I was 15, my parents were not “married” or sealed in the Temple,

but had been originally in a civil marriage ceremony. Not having been sealed

when my sister and I were born, we were not born “in” or “under” the covenant,

therefore, when my parents were sealed together when I was 15, my sister and I

were “sealed” to them as a family unit.

In the early days of the Church, before the sealing endowment was fully understood, occasionally two or more families would be sealed together and many people were sealed to Joseph Smith, the Prophet—many were women and most sealings were after he was dead. These were not marriages, but family units sealed together. So often, critics of the Church or people who simply do not know better, accept the worst, thinking something terrible, immoral and dishonorable was being done, which was not at all the case. You impinge the honor and high moral standing of good people when you pass on such tidbits you have not yourself researched and learned all the background information available.

Comment #2: “In Alma 11:1-20, we read of a Nephite proto-monetary system with exchanges for differing weights of pieces of metal. According to more than a few modern readers, the “plain” reading suggests that the Nephites had coins. Several decades ago, the Church began to add notes, cross-references, and chapter headings to the Book of Mormon text. To modern readers it seemed obvious that Alma 11 was describing coins, so the chapter heading including a note that this chapter detailed a system of “Nephite coinage.” The Book of Mormon text, however, never mentions coins and, upon closer examination, the text doesn’t suggest that the Nephites had coins. The “plain” reading was wrong and recent Book of Mormon editions have corrected the chapter heading to read “Nephite monetary system” Brad J.

Response: The word coin comes from Middle English and from Old French before that, which meant ‘wedge, corner, die,’ coigner ‘to mint,’ from Latin cuneus ‘wedge.’ The original sense was ‘cornerstone,’ later ‘angle or wedge’ (senses now spelled quoin, meaning “cornerstone”). Later in Middle English, the word evolved to mean a “die” for stamping money, or a piece of money produced by such a die.

John L. Sorenson claims, since no ancient coins were ever found in Mesoamerica, that the usage in the Book of Mormon did not mean money but a measuring system. However, the simple fact is that in Alma we learn that “And it came to pass that he did teach these things so much that many did believe on his words, even so many that they began to support him and give him money“ (Alma 1:5, emphasis added).

Now “money” has a specific meaning, and is not the same as a “measure.” In addition, “Yea, they did persecute them, and afflict them with all manner of words, and this because of their humility; because they were not proud in their own eyes, and because they did impart the word of God, one with another, without money and without price” (Alma 1:20, emphasis added). And also, “Now, it was for the sole purpose to get gain, because they received their wages according to their employ, therefore, they did stir up the people to riotings, and all manner of disturbances and wickedness, that they might have more employ, that they might get money according to the suits which were brought before them; therefore they did stir up the people against Alma and Amulek” (Alma 11:20).

Joseph Smith used the word “money,” and an 1828 dictionary meaning of “money” in New England meant “Coin; stamped metal; any piece of metal, usually gold, silver or copper, stamped by public authority, and used as the medium of commerce.”

However, the coup de grâce of this is found in Alma

11 when Zeezrom, evidently holding out his hand, said, “Behold, here are six

onties of silver, and all these will I give thee if thou wilt deny the

existence of a Supreme Being” (v22). We are not talking about weights and

measures here, but solid money that could be seen, felt and held—extended in Zeezrom’s

hand, evidently carried on his person in a pouch or pocket, and extended at

this dramatic money to confound Amulek.

Thus, playing to the crowd, Zeezrom held the money out before him toward Amulek. Whatever it was in his hand, the people could easily identify it, and it was worth significant value for Zeezrom to make his point of offering a lot of money to Amulek for the latter to deny the Christ.

If this was anything other than “coined” money, it simply would not have carried any significance in that moment and Zeezrom would have been unable to sway the people to his side, as was his intent.

Comment #3: “I’m at a loss about some controversy over the Wentworth Letter regarding Joseph Smith using a wrong sequencing of events or something. Could you straighten me out on this?” Redd H.

Response: I assume you mean when Joseph wrote that the first settlement in this land of the Western Hemisphere was when the Jaredites arrived, neglecting to include the actual first settlement was when Adam was ejected from the Garden of Eden and eventually at the end of his life when the meeting at Adam-ondi-ahman, which of course would pre-date the Jaredite occupation.

The problem arises over critics who look for something—anything—they can dig their heels into and yell “foul.” It is even very likely that the Wentworth Letter was a re-wording by scribes of Joseph Smith’s ideas which he wanted to convey. And most importantly, the letter, as few things are, was not intended to expose everything Joseph Smith knew. Instead, the Wentworth Letter was intended to be a basic introduction to the Book of Mormon and to the Restored Gospel.

As an example, does the letter’s neglect to mention Adam mean Joseph forgot about his settling here on the Western Hemisphere? Of course not. The context of the letter is limited. It is not about everything that has happened on this continent ever. The context is of a particular history—a history that started when the Jaredites arrived. The broad, sweeping language is probably the work of the scribes, who were evidently drawing on Orson Pratt’s 1840 Pamphlet. For instance, Pratt wrote “early settlement,” which was changed to “first settlement” for the Wentworth Letter. I imagine the scribes thought nothing of it doctrinally, but they may have thought the word “first” is more precise grammatically and therefore would sound more professional.