Continuing

with this last segment on another comment from a new reader, evidently

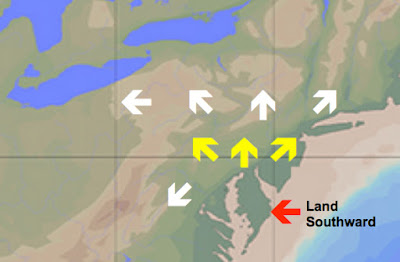

promoting his own book “Finding Zarahemla,” to which we are responding and

continuing with an understanding of this entire Delmarva Peninsula that

Franklin Reid claims was the Land Southward.

The

geologic background and development of this area simply does not fit the Land

of Promise and its many descriptions from the scriptural record. We continue

here with this development and bring it up to date to the time of the Nephites.

Middle Ordovician

Paleomap 485 Million Years Ago showing the Taconic Island arc complex

If we go back in geologic

periods, to a time when the current Delaware area was forming, it was a series

of tiny islands off a ragged, peninsula strewn east coast, during the period

known as Taconic Orogeny and referred to as Ancestral North America. Beginning

510 million years ago, the current Delaware area was a solid coastline

northeast of the Taconic Arc, with the Lauentian land mass along the east coast

subducting beneath the Taconic arc, and off the coastal area to the east was a

series of mountains.

The

eastern (northern) portion of Avalonia was sandwiched between both eastern

Canada and parts of Baltica. Contact

between Avalonia and Proto (New) North America progressed to the south and west over

the next 40 million years.

Ongoing collisions created the

Northern Appalachian mountains. The event is known as the Acadian orogeny (or sometimes the

Appalachian or Avalonian

orogeny)

According to Dr. Ron Blakely,

Northern Arizona University, there was a multi-step process that added New

England to Proto North America and added land to the coast as far south as the

Carolinas. This Taconic island chain began to collide with North America about 470 to 450 million years ago, the energy of ongoing impacts was

still raising mountains from Canada to Virginia 430 million years ago.

It should be kept in mind that

at this time, the Proto North America was straddling the equator and the

present east coast was actually the south then.

The

Iapetus Ocean, which had been the shoreline for Proto North America, is closing

as Western and Eastern Avalonia, following behind the Taconic arc, are heading

for collision with the recently-extended coast of Proto North America. The

first impact was against what is now Greenland and eastern Canada, then moving

southward, the collision zone moved through New York near the present Hudson

River valley. The Taconic mountain chain was created as the arc rode up and

onto the Laurentian landmass, a part of which was subducted below the Taconic arc. A wide swath of Iapetus Ocean seabed material will

be pushed onto this mainland as the Avalonian islands push against and onto

Proto North America.

Prior to

the Taconic orogeny, the "east" coast of what is now the United

States was located near the Hudson River valley, Philadelphia, Washington, DC

and extended to western South Carolina. The Taconic orogeny added land to Proto North America that

is now the western portions of New England and the Canadian Maritime provinces.

This collision added land and raised mountains southward through northern

New Jersey, south-eastern Pennsylvania, Virginia and North Carolina. The

orogeny ended about 445 million years ago.

Paleontologists have developed maps

of eastern North America covering the last 550 million years of geologic

history, with time slices of more than 100 maps of about 5-10 million years

apart, these images bring us up to the last ice age

Once

the east coast was formalized, about 370 million years ago, the eastern coast

from Main to Connecticut was filled with volcanic material and Iapetus Ocean

sediments as the land masses converged, forming a band of younger terrane

between the older Laurentian and avalonia terranes. It is also found in South

Carolina (Carolina Terrane) as well as north in New Brunswick and Newfoundland.

By

this time, the area of present day Delaware was pretty much set, which is

easily seen as a peninsula, not an island. And as already discussed in this

series, a peninsula with a “narrow neck of land” only 12 miles across which

does not fit Mormon’s day-and-a-half-journey width requirement (Alma 22:32).

In

addition, as stated earlier, the winds and currents of the Chesapeake Bay would

not have allowed Nephi’s ship “driven forth before the wind” to have even

entered, and the very shallow shoaling along the peninsula’s west coast would

not have allowed his ship to dock anywhere in the West Sea South (Alma 22:28).

With the entire eastern United States

to move into in an effort to escape the lamanite horde, why would Mormon and

the Nephites stand and fight somewhere in the Land Northward—after all, in

Franklin’s model, they could have retreated in any direction quite easily; and why

would those who did escape, go back into the Land Southward into the south

country rather than northward into the mainland interior?

Another

very important point is found in Mormon when we are told: “And the three hundred and forty and ninth year had passed away. And in

the three hundred and fiftieth year we made a treaty with the Lamanites and the

robbers of Gadianton, in which we did get the lands of our inheritance divided”

(Mormon 2:28)

When

Mormon and the Lamanite king entered into a treaty, and the Lamanites were

given the tiny area of the Land Southward in Franklin’s model, and the Nephites

were given all the land to the north, which encompasses over 220,000 square

miles in just immediately surrounding area as can be seen on the map above,

though the land to the north would not be limited even to that small of an area.

The

point is, in this scenario, with unlimited land easily accessible to the north

of the treaty line, why would Mormon and the Nephites stand and fight a battle

they could not possibly win against overwhelming odds when they could have continued

to retreat, which they had been doing for several years before the treaty

(Mormon 2:3,5-6,16,20) and after the treaty (Mormon 4:3,20-21,22; 5:5.7;6:1).

So why stop at Cumorah and fight a foe whose overwhelming numbers caused “every

soul was filled with terror because of the greatness of their numbers” (Mormon

6:8).

No,

it simply does not make sense to place the Land of Promise in an area like

Delmarva where there is no delineated Land Northward that did not contain the

Nephites and force them to fight a last, desperate battle they had no chance of

winning.

The

problem with writing about the Book of Mormon is when someone tries to sell a

setting that makes no sense related to the descriptive material of the

scriptural record. The Nephites were hemmed in within the Land Northward. They had

retreated as far as they could go. The Land of Many Waters, Rivers and

Fountains, which land also contained the Land of Cumorah and the hill Cumorah—as

Mormon tells us: “And I, Mormon, wrote an

epistle unto the king of the Lamanites, and desired of him that he would grant

unto us that we might gather together our people unto the land of Cumorah, by a

hill which was called Cumorah, and there we could give them battle” (Mormon

6:2), and “we did march forth to the land

of Cumorah, and we did pitch our tents around about the hill Cumorah; and it

was in a land of many waters, rivers, and fountains; and here we had hope to

gain advantage over the Lamanites” (Mormon 6:4).

First

of all, there simply is no location in Franklin’s Land Northward that could be

called a land of many waters, rivers and fountains. To reach any sizable water

source, it is 332 miles to Lake Erie, and also 332 miles to Seneca Lake of the

Finger Lakes which, by the way, are not fountains at all, nor are the Great

Lakes, which receive their replenishment from rainfall and snowfall, not from

natural fountains. What rivers supply the lakes are found in the sources far to

the north in Canada.

The

point is, you cannot look at a map, no matter how detailed it might be, and

decide where the Land of Promise might have been. This is especially true when

one starts out looking for a peninsula as the location—since a peninsula is not

how the entire Land of Promise is described, but as an island (2 Nephi 10:20).

Consequently,

one then cannot start looking for where Zarahemla was located when one starts

out in the wrong area to begin with—after all, the only way to find the Land of

Promise is to trace Nephi’s ship’s course as he describes it, i.e., a ship that

is driven forth before the wind (1 Nephi 18:8,9), that is, being pushed forward

by wind currents, and obviously having to follow sea currents which the winds

direct.

In

1828, “forth” meant “forward”; and “driven” meant urged forward by force,

impelled to move, constrained by necessity, and “before” meant “in front

of.” That is, “driven forth before the

wind” meant exactly what is sounds like: Nephi’s vessel was “moved forward by

the force of the wind” as well as being constrained within that path, i.e., it

could not go elsewhere than where the wind blew it within the ocean currents.

Since

winds move ocean currents, the idea is that Nephi is telling us that his vessel

was driven forth before the wind along the ocean currents also driven forth

before the wind. All we have to do, then, is follow the ocean currents and

where the winds blew from off the southern coast of Arabia to follow the path

Lehi took and, therefore, where he landed. And those currents certainly did not led down around the horn of Africa through the worst ship's graveyard on the planet, nor up local rivers along the eastern seaboard of the U.S. against winds and currents as we have explained here many times over the past six years.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment