Diagram

of one of the burial mounds in Spring Branch Village Site, Kansas Valley,

Kansas, showing in the center of the burial mound (#2) an area of ashes,

calcined and natural human bones, which shows cremation, a factor that was

adamantly against the Law of Moses, which the Nephites lived for over 600 years

in the Land of Promise

It is interesting that while the Mounds in the

United States are somewhat representative of burial mounds found around the

world, there are no mounds in the location from which the Nephites and their

ancestors came and nothing in the modern or ancient world to tie these two

together. Theodore Brandley, like nearly all the other North America Land of Promise theorists, tries to tell us that the Mounds found throughout the Mississippi Basin, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes, are evidence of the Nephite nation in the Land of Promise. The problem is, not only is there no mention of mounds in the Book of Mormon, there is no history among the Jews in Jerusalem nor the Hebrews before them or anywhere round about that they ever built, used or even knew of such mounds.

Nicholls Burial Mound in Wisconsin. During

the 1920’s and 30’s the Milwaukee Public Museum set out to answer these basic questions

by excavating different mound types across the state. While at Trempealeau, the

Milwaukee team excavated both conical and animal shaped mounds. The Nicholls

Mound was the largest of the conical mounds in the area

Yet, wherever people

have lived, there are places where they have left their dead. These native-American

cemeteries, or burial mounds, were first formed 1500-2000 years ago. This

particular mound area, the Valley City burial mound complex, consisted of

fifteen circular mounds and five linear mounds. The mounds were made by stripping sod from a circular area. A burial chamber was excavated in the center of this area and individuals placed inside in various ways depending on their age, sex, or social status. They were positioned on their backs, sides, face down, sitting, or even standing. Jewelry, tools, food or symbols of their associated clans may have been included. Sometimes only the bones were buried in bundles or baskets. With the passage of time, burial customs changed and the use of burial mounds was discontinued.

The mounds were formed when dirt was used to fill and cover a burial chamber (yellow layer). Later, others were buried in the same mound and more dirt was added, increasing its height and width (brown layer). This may have occurred several times over hundreds of years (black layer). Some mounds were used for over a thousand years and may contain up to thirty-five individuals!

While not all mounds contain burials, most do, like in the larger conical mounds appearing from the larger conical mounds of the Hopewell Culture. Later animal-shaped or “effigy” mounds sometimes contain burials, but some that were excavated did not. The two effigy mounds excavated in Perrot State Park did contain several burials. Platform mounds of the Mississippian Culture appear to have been constructed primarily as foundations upon which houses were built. A series of these overlooking the Village of Trempealeau were never excavated.

Map showing the Hopewell influence of the Hopewell Cultures, from Wisconsin to Mississippi to western New York

In Wisconsin surveys suggest somewhere between 15,000 and 20,000 mounds were built, with some 80% plowed down and destroyed through town and city development in the last 150 years. Mounds throughout the U.S. were constructed in a variety of forms, at different periods of time, and for different reasons. The earliest mounds of the Hopewell Culture are round or “conical” and were constructed primarily as burial tombs. Later “Effigy” mounds were built in shapes such as birds and other animals, only a few of which we recognize. Others are more abstract, and some are geometric. While some of these do contain burials, some do not, and their purpose is unknown. Many of the mounds found throughout the U.S. were built as tombs with the mound serving not only to dispose of the dead but the communal effort of mound construction also served to reinforce social bonds.

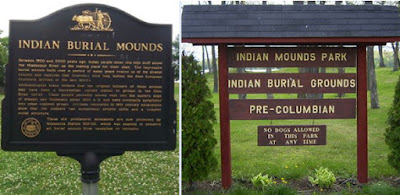

Indian burial mounds are scattered all over the Great Lakes,

Mississippi Valley, eastern U.S. and Heartland area—they have absolutely no

connection to anything Jewish, Hebrew, Jerusalem, Mesopotamia or Nephite in any

period of time

The mound itself stood as a

marker not only of the dead but of the living culture, clarifying to all that

this is our land and that of our ancestors. It is estimated that it took to

build a mound for the burial of one person or a family about 20 people with

basket loads of earth in one day. Larger, more elaborate mounds obviously took

more people and/or more time.In the fall of 1685 Nicholas Perrot and a small party of Frenchmen beached their canoes at Trempealeau, Wisconsin, where they built a protective shelter in preparation for winter. Several weeks earlier Perrot and his men had left Green Bay and crossed Wisconsin via the Fox and Wisconsin Rivers to reach the Mississippi Valley. The purpose of this expedition was to establish alliances with the Ioway and Dakota Indians in order to expand French interests in the fur trade market. Although Perrot’s venture was not the first French excursion into the upper Mississippi Valley, his was the first attempt to establish a foothold in this region. In the spring of 1686 the Trempealeau site was abandoned for a more advantageous location along Lake Pepin where Perrot built Fort St. Antoine. Over the next thirty-five years French economic fortunes in the upper Mississippi Valley waxed and waned. It was not until 1731, and the end of the Fox Indian wars, that the French under the command of Rene Godefroy sieur de Linctot returned to Trempealeau and established another trading post.

The Hopewell Culture influence extended from the Rocky Mountains to the Appalachians, core areas were located in restricted areas of Ohio and central Illinois. At each of these two centers, large mound complexes consisting of round “conical’ mounds and square or circular embankments existed representing enormous works of labor and social cooperation. Excavation of some mounds in the 19th and early 20th centuries found evidence of elaborate burial rituals. Often, Hopewell mounds were constructed over wood and bark structures, many of which were burned. Within rectangular pits, burials of several to many individuals were placed prior to mound construction. These included adult men and women as well as children.

Left: Effigy Mounds in Wisconsin; Right: Map

Effigy Mounds in Mississippi Valley

It is known, for

example, that the Hopewell Culture dates from about A.D. 100-400 and that the

Effigy Mound Culture dates from about A.D. 700-1100. Since about the 1940’s,

archaeologists have shifted emphasis from mounds to camp sites, though very

little work was done in the Trempealeau area with the exception of excavations

by the State Historical Society in the mid 1960’s. In the meantime, a number of

research questions had arisen. For example, did the people who built the mounds

live adjacent to them? If so, did they live there all year, or only during the

summer? Did they craft the special burial artifacts or where they traded in as

finished artifacts from other Hopewell centers? Research conducted at the Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center at Trempealeau in 1996, where shovel testing found a continuous scatter of camp debris showing continual use from about 4,000 to 1,000 years ago (2000 B.C. to 1000 A.D.) The second Native American camp excavated is on the point immediately west of the Park nature shelter. Here shovel testing and excavations found some disturbances from historic camping, but much of the site was intact. The soils reflected a prairie environment, with artifacts dating from about 4,000 to 500 years ago, including a series of pits that contained pottery, a grinding stone, arrow shaft straightener, and other materials of the Oneota Culture.

Top: Mississippian culture and house; Bottom: A Oneota Long House for community living and gatherings. This is hardly the kind of living and conditions one would expect to find people building coming from Jerusalem in 600 B.C., where entire cities were made of stone and very advanced construction capabilities

The Oneota were

the first intensive corn farmers in the region. Although some Oneota mounds are

known from other areas, McKern’s excavations of the Trempealeau mounds did not

find Oneota burials. The 1996 investigations at the French post encountered a

midden that contained thousands of bone fragments from mammals, including

buffalo, elk, deer, black bear, raccoon, and beaver with about half being

burned, which often reflects cooking to extract marrow and other nutrients and

suggests winter occupation. This agrees with the French records for both Perrot

and Linctot as having been at Trempealeau during the winter season. In

addition, mixed directly with the bone were several artifacts from the French

era. These deposits demonstrate that the bone is from a French occupation although

it is not yet known if the post dates to the Perrot camp in 1685-86 or the

Linctot occupation in 1731-32.The conclusion of this huge project entailing massive effort by large numbers of workers, showed a multi-component site with Paleo-Indian Archaic, Woodland, Oneota and early historic occupations. The Hopewell Culture existed in the Midwest from about 100-400 A.D. Although Hopewell influence extended from the Rocky Mountains to the Appalachians, core areas were located in restricted parts of Ohio and central Illinois. At each of these two centers, large mound complexes consisting of round “conical” burial mounds and square or circular embankments existed representing enormous works of labor and social cooperation. Excavation of some mounds in the 19th and early 20th centuries found evidence of elaborate burial rituals. Often, Hopewell mounds were constructed over wood and bark structures, many of which were burned. Within rectangular pits, burials of several to many individuals were placed prior to mound construction. These included adult men and women as well as children.

Jews and Hebrews buried their dead in stone

sepulchers cut into rock

Once again, after all

of this, we need to keep in mind that burial mounds have never been a part of

the Jewish, Israel, or Hebrew cultures of the Middle East, and certainly has no

mention of such in the Book of Mormon for either the Jaredies, Nephites or

Lamanites.Yet the fiction remains, that this highly developed culture of Lehi’s colony, coming from the highly advanced Jewish state that built with nothing but stone for buildings, houses, temples, and public complexes, of which Lehi, Nephi, Sam and Zoram were all very familiar, has no correlation with burial mounds and a total lack of stone construction in the Heartland, eastern U.S. or Great Lakes areas before, during or after the Nephite period.

Del, it does not seem to me that you wrote that last sentence correctly: "Yet the fiction remains, that this highly developed culture of Lehi’s colony,... has no correlation with burial mounds and a total lack of stone construction in the Heartland, eastern U.S. or Great Lakes areas..." It sounds like the "no correlation" is the "fiction that remains" instead of obviously the other way around.

ReplyDeleteYet the fiction remains among Great Lakes Theorists, that this highly developed culture of Lehi’s colony, coming from the highly advanced Jewish state that built with nothing but stone for buildings, houses, temples, and public complexes, of which Lehi, Nephi, Sam and Zoram were all very familiar, built only with sticks and grass in the Land of Promise; and, too built burial mounds which had nothing to do with Hebrew heritage, Jerusalem, Israel or Mesopotamia from “whence they came.” In addition, though they came from the building of magnificent stone structures, not a single ancient construction of anything can be found in all of the eastern U.S., Heartland or Great Lakes made of stone. One should be led to say that the Great Lakes is certainly not the Land of Promise, rather than continue the fiction that it is.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteWOULD YOU LIKE DOCUMENTS AND PICTURES OF MISSING UNDOCUMENTED ADENA MOUNDS WITH A PITTSBURGH - CLEVELAND CONNECTION

ReplyDelete