The first American-English dictionary was published by Noah Webster in 1828, called An American Dictionary of the English Language--and after he died in 1843, George and Charles Merriam, who had founded the G&C Merriam Co. in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1828, bought the rights to An American Dictionary of the English Language from Webster's estate, and today is the direct lexicographical heir of Noah Webster. Today (since 1982) that company is known as Merriam-Webster, and is the foremost publisher of language-related reference words, as well as the longest producer of dictionaries in the world.

It should be noted that much work has been achieved by linguists and lexicographers regarding dictionaries; however, not all dictionaries are the same. As an example, the Oxford English Dictionary contains spelling and definitions of words that are oriented toward British English,while the Webster dictionary contains spelling and definitions more oriented to American English.

Consequently, since the Book of Mormon was published initially for Americans, and even more specifically those living in the New England area where the Church was first organized, American-English would seem to be the predominant meaning of words used by Joseph Smith in his translation,who himself, like Noah Webster, was from New England.

However, in a never-ending attempt at understanding the interpretation of the scriptural record in Joseph Smith’s translation, various linguists, writers, and theorists make unusual and sometimes downright unbelievable claims. As an example, on Kirk Magleby’s Book of Mormon Resources website, in an article entitled OED on Necks of Land, the author quotes heavily from Royal Skousen’s "The Original Language of the Book of Mormon: Upstate New York Dialect, King James English, or Hebrew?" in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (3.1).

Skousen, our readers might recall, a Professor of Linguistics and English Language at BYU, has been for some time a believer that the Book of Mormon has many errors in it and should be updated and the language considerably changed or altered to fit his findings according to his Analysis of Textual Variants of the book of Mormon (a Six-Volume Set, Interpreter Foundation, 2017). For background on Skousen’s project and the many errors Skousen makes, see our 11-part Series on “The Critical Text Project or Webster’s 1828 Dictionary: An Interesting Comparison” (appeared between Saturday, December 5, 2015, and Tuesday, December 15, 2015, in this blog).

In any event, the website article is fraught with erroneous conclusions and misleading information regarding the scriptural record and its interpretation.

According to the article, which is supportive of the OED (Oxford English Dictionary) over the 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language, which we use throughout our blog articles when defining words Joseph Smith used in his interpretation, states: “The indispensable dictionary for exegesis of Mormon's and Moroni's abridgments can only be the incomparable Oxford English Dictionary commonly called the OED. Textual scholars such as Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack use the OED extensively.” Now “exegesis” means the “critical explanation or interpretation (explanation and meaning) of a text, especially of scripture,” so the article as well as Skousan and Carmack, claim that any question about the meaning of a word in the Book of Mormon should be referred to the Oxford Dictionary for understanding.

First of all, by way of background, Magleby introduces a reference to an earlier article he wrote entitled “Early Modern English” in which he begins by saying that 450 A.D. was the beginning of Old English, which continued until 1100-1170 A.D., when Middle English began, continuing until 1300 A.D., followed by Late Middle English through 1470-1500 A.D., which was replaced by Early Modern English until 1670-1700 A.D. (possibly 1800 A.D.) This was finally replaced by “Modern English aka Late Modern English which has become Earth's lingua franca.”

He then goes on to state that in 1611 the first edition of the King James Version of the Bible was published in Early Modern English, with predecessors including the Tyndale New Testament in 1526 and the Coverdale Bible in 1525. In 1755 Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language helped standardize the Modern English we use today. And that the first edition of the monumental Oxford English Dictionary was published in 1928 in ten bound volumes. The most cited work in the OED: various editions of the Bible. The most cited author: William Shakespea/re. Shakespeare's most cited play: Hamlet.

In the early 1800s, American life was centered around the home, church

and school and established on Biblical and patriotic basis

Webster opposed Horace Mann’s progressive reduction of the meaning of religion and the constitution in his educational promotions. It was Horace Mann who, in the 1840s, removed the Bible and its sacred purpose from the schools, not the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1960s. Webster was opposed to this European pilgrimage of Mann and his contemporaries planting the alien seeds of foreign ideologies and philosophies of education on American soil. Webster believed in the American independence from European “maxims of government” and labored extensively to eliminate them from American schools and philosophy—an idea that stemmed from the New England mindset of Americans, of which the Smith family was part.

Webster’s plea in his 1828 dictionary stated: “This country must be as distinguished by the superiority of her literary improvements, as she is already by the liberality of her civil and ecclesiastical constitutions. Europe is grown old in folly corruption and tyranny—in that country laws are perverted, manners are licentious, literature is declining and human nature debased. For America in her infancy to adopt the present maxims of the old world, would be to stamp the wrinkles of decrepid age upon the bloom of youth and to plant the seeds of decay in a vigorous constitution.”

Webster was adamant about not repeating the mistakes of Europe in the development of America. In that effort, he was also adamant about having a language that represented America and how it was then being spoken in New England (by the Smith family and all New Englanders), and to alter the words to the American vocabulary and not that of England. This was such a noticeable change from the English spoken and defined in Europe, that he developed his dictionary, which was explicit on the spelling and pronunciation of words, as well as their meaning. Webster was aggravated by the introduction of English understanding of words into the American lexicon.

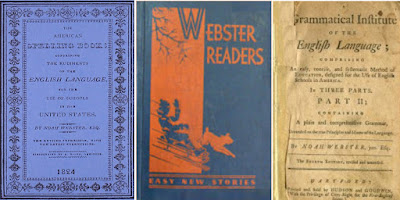

Webster’s “Speller,” “Reader,” and “Grammar” books in all American

schools in early 1800s

In all of this, Noah Webster was not so much in creating something different, but in preserving the American method and use of the English language that existed in the area of American concentration, that is, in the New England area of the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Webster was specifically displeased with the English language attempt to avert the meaning of the new American Republic to a “democracy” in which, as the eminent British scientist Joseph Priestley put it in 1800, meant that only Democrats were Americans, and any other political ideology was subversive and against the American Constitution, which he called the American Democracy. English, as understood in Britain, had very different meanings and interpretation of government and government philosophy than that of America and Americans. Webster wanted to preserve those differences, since they were the very core and basis of the Constitution and the American government. His dictionary accomplished that and numerous other Americanisms that were missing from the English dictionaries, including the Oxford English Dictionary.

To say, as Magleby and others do, that Joseph Smith’s writings reflect better the OED than the Webster interpretations of language is far from accurate, and extremely misleading if not downright disingenuous. Noah Webster grew up 90 miles from where Joseph Smith grew up. They knew and used the same language and the same interpretation of that language. The 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language contained not only the language Joseph Smith knew and used, but it was also the dictionary he chose to use for the School of the Prophets classes in the teaching of the brethren about the gospel and its meaning.

The fact that Magleby claims: “The indispensable dictionary for exegesis of Mormon's and Moroni's abridgments can only be the incomparable Oxford English Dictionary commonly called the OED. Textual scholars such as Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack use the OED extensively,” should suggest to us that Magleby and the others who rely on the OED are simply out of touch with the reality of Joseph Smith and his times in New England America.

It is also interesting that Noah Webster claims in his introduction to his dictionary that he felt the Spirit of God prompting him in his work, and the fact that the dictionary appeared just two years prior to the publication of the Book of Mormon ought to suggest to us that the Lord had his hand in the matter.

(See the next post, “Webster vs. Oxford English Dictionaries – Part II,” regarding the difference between Britain English as found in the Oxford English Dictionary, or American English as found in Webster’s 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language)

No comments:

Post a Comment