It should be kept in mind that that the entire Mississippi River from its source in Itasca Lake in Minnesota, to the Gulf, even today with all the work that has been done on the river by the Corps of Engineers to make and keep it open to shipping, was recently the scene of a paddle wheel vessel called “The American Queen,” a $65-million replica of the early paddler wheelers, that ran aground on a sand bar and was stuck there from 5am on Monday until 7pm on Wednesday, for more than 3½ days, while not even huge tow boats could free the paddlewheeler, until three dredges, a rising river and pumping fuel out of the vessel and lighten it eventually freed it (UPI story, June 19. 1995; Carol Barrington, “Sandbar Dashes Nary a Spirit,” Chicago Tribune, July 2, 1995).

The River’s history began with ice sheets during what is called the Illinoian Stage, blocked the Mississippi near Rock Island, Illinois, diverting it to its present channel farther to the west, which is the current western border of Illinois. The current man-made, and now abandoned, Hennepin Canal roughly follows the ancient channel of the Mississippi downstream from Rock Island to Hennepin, Illinois. South of Hennepin, to Alton, Illinois, the current Illinois River follows the ancient channel used by the Mississippi River before the Illinoian Stage (E. D. McKay and R. C. Berg, “Optical Ages Spanning two Glacial-interglacial Cycles from Deposits of the Ancient Mississippi River, north-central Illinois, Geological Society of America Abstracts (with Programs), vol.40, no.5, 2008, p78).

The Coastal Delta where the Mississippi

River empties into the Gulf of Mexico has changed drastically over the years

from ancient BC times to today; however, it should be noted, that this is from

the emptying of five major river sediments being moved downriver to its mouth—the

rest of the river has not changed anywhere near that drastically, though

changes have been noted

The point is, the Mississippi River has basically been in the same general area. For thousands of years and what small changes in actual route have not affected its depth, width, or problems for deep sea sailing vessels to move up the river. Meldrum and other theorists who claim things about the Mississippi obviously ignore the facts by those who have studied this river for more than a hundred years.

For those looking at such theorists’ ideas, it is important when evaluating different models and opinions connected to their theories, to evaluate them against known facts regarding the areas and physical features as well as the geologic support for their point of view. This is especially true when theorists like those who promote the Heartland of the U.S. as the Land of Promise insist that the Mississippi River is the Sidon River of the scriptural record.

So much is known about the distant history of this river that knowing such facts aids one in determining claims made by such theorists as Rod L. Meldrum and other Heartland theorists. The important point is that the Mississippi River does not match the descriptive terms given to describe the Sidon River and its location and source, yet this fact—not opinion—seems to have no meaning to theorists who want to place their Land of Promise in the contiguous United States.

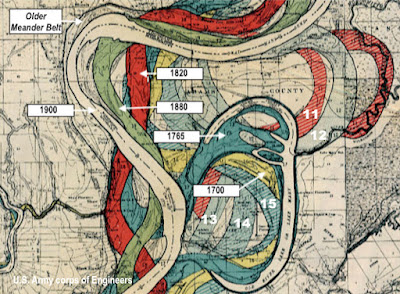

The Mississippi Meander Belt, showing previous courses of the

Mississippi River. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has listed 20 different

courses, with four older than the Meander Belt. White numbers reflect the

previous courses that are undated, but preceded the last date shown going

backward into antiquity

It should also be noted that the River’s course in Louisiana somewhere between 3000 BC to 1000 AD followed what is today called the Bayou Teche, a 125-mile long waterway running along the Coteau Ridge as its west bank from Port Barre to New Iberia in south central Louisiana, about 30 miles west of the present Mississippi course a little north of Lafayette, about 20 miles north of the Gulf. This was the original Mississippi course through Louisiana at the time the river developed a delta it is believed about 2800 to 4500 years ago. It should also be understood that the river then was carrying nineteen times the volume of water compared to the present-day flow of the Mississippi River—that is, 11,267,000 cubic feet of water per second (Mississippi today is 593,000 cubic feet per second); compared to the largest river flow today, which is the Amazon River at 7,380,765 cubic feet).

It would be interesting to know, from those who claim Lehi sailed up the Mississippi River from the Gulf of Mexico, how exactly they did that in a vessel “driven forth before the wind.” After all, this would have been especially difficult since winds tend to blow along the course of a river’s direction, or in this case blowing southward, making Lehi’s ship having to sail against the wind and against the fastest known current now in existence, with only sail power to move the ship.

In addition, the River’s actual present course was about the same throughout its history, with the change in the southern extremity through a portion of Louisiana, which, in 1000 AD, was finalized as we see it today. However, in 3000 BC, it was affirmed to be in its present position beyond central Louisiana. Anciently, as now, the Mississippi River began heading northward from the North Arm of Lake Itasca and continued northward for about 15 miles to an area called Mississippi Headwaters, then turned east to Lake Irving and Lake Bernidji, continuing east to Stump Lake, then heading southeast to the Leech Lake Reservation, a composite of several lakes of which the Mississippi passed through, then bent toward the south about 160 miles north of Minneapolis and headed southward to wind through what is now the Twin Cities and on its main course direction to St. Louis, and down to Cairo, Illinois where it picked up the Ohio river at the confluence before continuing on southward.

Now, with all this in mind regarding the completely known background of the Mississippi River and the surrounding countryside, let’s take a look at Meldrum’s claim that the Mississippi River is the River Sidon of the Book of Mormon

Top: Baton Rouge is about 245 miles

upriver form the Mississippi Delta and mouth of the river; Bottom: The Shallows

above Baton Rouge from the Istrouma Bluff to Solitude Point, along this stretch

of river had to be dredged and deepened by the Corps of Engineers in order for

shipping to proceed beyond Baton Rouge northward

From Baton Rouge to Wilkinson Point, where Southern University is located, then to the west around Thomas Point, which is a hairpin curve—for some geologic or hydrologic reason not understood, the bends of the Mississippi through south Louisiana do not make smooth rounded curves like they do to the north; the bends come to sharp points, blind corners and tight turns. In addition, at this point, the river enters “full throttle” going first in one direction, and then makes chaotic swirly changes to head in the opposite direction, causing difficulty in steering and maneuvering up the river. At Mallet Bend and back east toward Mulatto Bend the river was very shallow in ages past clear up to the point where the Corps of Engineers dredged the river to allow paddlewheel boats to pass. Before that time, no kind of vessel from the sea could get beyond Baton Rouge.

(See the next post, “Where Theorists Go Wrong – Part IV,” to see how in not understanding the history of an area, that it does not automatically qualify for a Land of Promise site, because of its name or its proximity to other sites)

No comments:

Post a Comment