Obviously, since the middle east is mostly desert outside the narrow, curved, fertile crescent, the camel has always been the ideal mode of transportation and conveyance of goods, supplies, and products. The reason for this is partly found in the unique legs and feet of the camelid.

A camel’s feet are not hooves and

are strongly adapted for the desert environment. The spreading toes help it not

to sink in shifting sands while thick sole in a camel provides a hurdle against

the summer sands, and saves the camel from being burned when it crosses the hot

sand

The camel is nicknamed "the ship of the desert" because they walk like the motion of a rolling boat—they move both feet on one side of their bodies, then both feet on the other side, giving them an unusual gait. In addition, their thick coat reflects sunlight, which helps to keep it from overheating in the hot, dry deserts. The animal also has long legs that help keep their bodies farther away from the hot ground, allowing them to walk long distances across desert sands.

As worthwhile and valuable the camel was to the Jaredites in both their Mesopotamian world, and in the trek to the sea that divided the land, they had only limited use in the Land of Promise, since whether one is looking at Andean South America, Mesoamerica, or the Heartland/Great Lakes in North America, there would be little sense in using a camel. On the other hand, there are certain areas where camels could not be used at all, and that is typically in the mountainous regions, as depicted in the scriptural record that saturated the Land of Promise: “There shall be many places which are now called valleys which shall become mountains, whose height is great” (Helaman 14:23). Even the earlier mountains that existed before this time in the land were tumbled into pieces (1 Nephi 12:4), or laid low, and became like valleys, the rocky terrain that had existed would still exist, just at lower or flat levels—that is the rocks now lad low and the rocks rent and the plains were broken up (1 Nephi 12:4), all of which would make footing difficult for a camel.

Camels were used for

riding across the desert

All of this among the Jaredites led to the two animals described in the scriptural record as the curelom and the cumom (Ether 9:19). Now, the nature or type of animal these two were, we are not told, other than that they were on a par in value to the Jaredites (useful to man) as the elephant, and more so than the horse and ass (donkey). There were also “wild asses” in Biblical times (Asinus hemippus), a “swift and untamable animal,” equaling the speed of the gazelle, that frequented the deserts of Syria, Mesopotamia, and northern Arabia. The modern donkey spring from the wild ass known as the Asinus vulgaris, a much slower and docile animal called “hamor” in Hebrew, and was an “unclean” animal since it did not chew its cud, but made up a considerable portion of wealth in ancient times (Genesis 12:16;30:43).

Camels were used for carrying supplies, products and provisions across

the desert

Neither of these animals could be bred from the animals existing in Mesopotamia in Jaredite times!

In addition, the Mesoamerican theorists point to the sloth, or giant sloth, and the tapir, though neither meets the criteria found in Ether. In fact, in looking at today’s sloth (something like a monkey) or a tapir (something like a pig) one hardly sees any similarity to the description in Ether. On the other hand, John L. Sorenson claims a “giant sloth” was involved—an animal the size of an ox, with long curved claws, likely an adaptation for foraging for grabbing branches and stripping foliage from tree limbs, as well as for protection from predators.

The giant sloth (and today’s sloth) were and are endemic to South America, not Mesoamerica, with the giant sloth becoming extinct, according to paleontologists, 11,700 year ago. Hardly living during Jaredite times (2200-2100 BC). In addition, the giant sloth had large, lumbering bodies, with large hind feet, enabling them to stand on their hindquarters to reach high into trees for forage. No giant sloth was ever recorded or known to be domesticated, be ridden or carry burdens.

Left: Tapir, which prefers a moist, dense forests, in temperate regions

of the Southern Hemisphere (South America), and is an animal that can be

domesticated and enjoys human contact, but can also be highly aggressive to

both other animals and to humans, with a tendency to attack rather than

retreat; Right: Sloth, which is a wild animal and are not domesticated, and are

not to be held or touched by humans

While both of these animals have worth to man, that worth is only after they are killed.

In addition, while the sloth and tapir may well have been unknown to Joseph Smith, himself and his ancestors being farmers, who knew about most animals of their day, he certainly would have heard of the Buffalo and Mountain Goat. On the other hand, in South America, are two animals that are extremely well known to be of great worth to man, and have been for thousands of years, yet were completely unknown in North America until well into the 20th century, more than a hundred years after the publication of the Book of Mormon and of Joseph’s death.

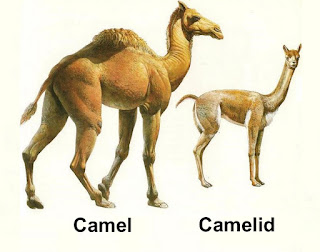

The camel was brought to the New World by the Jaredite, with which they bred

to deve3lop the smaller, more durable in non-desert environments, and known as

a camelid

The original New World animals were the guanaco and the vicuna, from which descended both the llama and the alpaca—two animals with a very long history in Andean South America. They are native to the high puna of the South American Andes—a montane grassland and shrubland of the high central Andes, and specifically the regions of Ecuador, Peru, western Bolivia and Chile, as well as peripherally Argentina and Colombia.

These two animals would have been bred by the Jaredites from the camels they brought to their land of promise, especially needed after finding the mountainous regions of the area and the difficulty camels would have had in the rocky terrain. These were the two animals mentioned in the Book of Ether that were unknown to Joseph Smith who used their Nephite or Jaredite names when translating the Plates.

(See the next post, “The Jaredite Animals in the Land of Promise – Part II,” regarding the development of the two animals mentioned in the Book of Ether and unknown to Joseph Smith when he translated the Plates)

I talked to a stanch North American model supporter the other day and after telling him what the 2 unknown animals were he said no that can't be true. They must be some sort of elephant because they are mentioned in the book of Ether and not in the days of Nephi. I told him the elephants were already mentioned and so it couldn't be them.

ReplyDeleteThey really have no place to run on this issue. By accepting the NA model they don't have any animals that fit the description at all.

Absolutely correct. They do like the Bison and Mountain Goat, though. The fact that those animals were not in their area of their Land Northward notwithstanding.

ReplyDelete