Was the

Isthmus of Panama once submerged and did the Pacific Ocean have a seaway

through to the Atlantic Ocean?

A Central

American Seaway allowed for a warm, salty water inflow from the Caribbean to

the Pacific, and a cool, low-salinity water outflow from the Pacific to the

Caribbean

It is claimed by Manuel A. Iturralde-Vinent, of the

National Museum of Natural History in Cuba, that in

order to summarize the evolution of the Caribbean Seaway, this is presented to

illustrate the history of topographic barriers between North and South America,

and their bearing on the history of marine flow across the area. This Seaway is

here understood as a truly oceanic basin located between the North and South

American continental landmasses. This seaway represents a linkage between the Pacific

and the Atlantic Oceans.

Also

according to Michael Xavier Kirby, of the Center for Tropical Paleoecology and

Archaeology, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, and Douglas S. Jones and

Bruce J. MacFadden of the University of Florida, the palaeogeography of Central

America has changed profoundly…from a volcanic arc separated from South America

by a wide seaway, to an isthmus that connected North and South America. The

formation of the Isthmus of Panama was important because it allowed the mixing

of terrestrial faunas between the two continents, as well as physically

separating a once continuous marine province into separate and distinct Pacific

and Caribbean communities. The formation of the Isthmus of Panama also

ultimately led to profound changes in global climate by strengthening the Gulf

Stream and thermohaline downwelling in the North Atlantic.

And according

to Daniela N. Schmidt of the Department of Geology, Royal Holloway University

of London and Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, in her work The closure history of the Central American

seaway: evidence from isotopes and fossils to models and molecules, the rise of the Panama

Isthmus was the last step in the closure of the circumtropical seaways. The closure of the Panama Isthmus had

fundamental consequences for global ocean circulation, evolution of the

tropical ecosystems and potentially influenced the switch to the modern ‘cold

house’ climate mode. The Atlantic and Pacific marine ecosystems became gradually

separated whereas terrestrial organisms suddenly had the means to migrate

between North and South America. Combining high-resolution geochemical proxies for the closure history with data on fossil distributions and genetic data provides independent evidence on the closure history. These datasets provide new boundary conditions for Earth System models to simulate the effects of palaeoceanographic change on global

climate and allow exploration of hypotheses for the Northern Hemisphere glaciation.

In addition,

according to Hermann Duque-Caro, in his 1990 Stratigraphy paleoceanography and paleobiography in northwest South

America in the evolution of the Panama Seaway, "Today, the Panama Isthmus

blocks the flow of Pacific waters into the Atlantic. When this land bridge was

submerged, Central America consisted of a complex island-arc archipelago

peninsula with several marine corridors and basins. During the initial uplift

of the Panama sill to upper middle bathyal depths, and subsequent blocking of

the deep-water flow through the seaway, changed bottom-water circulation and

sedimentation in the coastal areas of Central America as discovered by the deep

sea drilling mentioned in the last post.

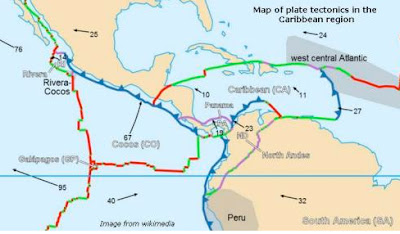

Map

of plate techtonics in the Caribbean Region. Their movement was responsible

for the closing of the Central American Seaway

According to

Matthew E. Kirby, Department of Geological Sciences, Cal State University, as part

of the Central American volcanic arc, the Panama microplate formed through

subduction of various oceanic microplates that lie between the Cocos and Nazca

plates to the south, the Caribbean plate to the north and the South American

plate to the east (note the tectonic plate map above).

The

Atrato Seaway between the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean through the

Panama Canal Basin as described by Kirby and MacFadden, often referred to as

the CAS (Central American Seaway), claimed by Duque-Caro to have been at least

500 feet deep

The closing

of the Central American Seaway changed the boundary conditions of the oceans

and created a state of the oceanic and atmospheric system. With the rising of

the isthmus, it blocked the exchange of tropical water masses between the

Atlantic and the Pacific and triggered, or strengthened, the North Atlantic deep

water production, initiated the Caribbean Current, strengthened the Gulf

Stream, and therefore changed the global distribution of deep water masses and

heat salinity, which intensified the circulation causing the buildup of

sediment drifts in the Caribbean and deepened the Barnes-Apure Basin in the

basement of Guiana, along the northern Barinas-Apure Basin of Venezuela, and

the Llanos Basin of Colombia, and later in the North Atlantic.

With the closing of the Central American

Seaway, there was a cutoff of the inflow and outflow between the two oceans,

and a strong northward flow of warm, salty water with more heat released out of

the north into the atmosphere

The existence of this Atrato Seaway (Central American Seaway) did not, however, as these

studies verify, change the water circulation in the South Pacific and

along the South American west coast. Though it likely resulted in the central

Pacific counter-current flowing into the Caribbean.

No comments:

Post a Comment