Continuing

from the previous post regarding the importance that the lack of metallurgy in

Mesoamerica is when considering where the Land of Promise truly was located.

Also continuing with the comments of John L. Sorenson, the so-called guru of

Book of Mormon Land of Promise geography, that are meant to lessen and even

question the meaning of the use of “metal” terminology in the scriptural

record. It is important to understand that simple comments, like Nephi making

swords like that of Laban, often required effort, learning, and achievement. In

reading the scriptural record, we often glaze over these extreme events and

accomplishments of both Nephi, and these early Nephites in all they

accomplished without really considering what was involved.

As

an example, it should also be kept in mind that sword making is a fine art. In

some cultures, the sword maker’s work was as highly sought after as was Antonio

Stradivari in 17th and 18th century Italy for his

violins, violas, cello, and string-making abilities. What Nephi knew about

swords is neither mentioned nor implied, however, since weapons are the

mainstay of the young in any culture, it can probably be assumed Nephi would

have known something about the properties of swords in his youth and early

metallurgical days.

As

an example, before steel was known, swords were made primarily out of bronze, a

combination of copper and tin, with the higher amount of tin (about 20%) made

the sword much stronger, though brittle and subject to breaking, while the

lesser amount of tin (about 10%) made the sword less likely to break, but

softer and more likely to bend in battle--thus early swords were often wide to keep them from bending.

Swordsmiths in China favored the

higher amount of tin with their copper, and the swordsmiths in Europe and Asia

preferred lesser amounts of tin in their mixture—thus, in the early eras,

Chinese swords were narrower, while the European and Asian swords were wider,

even to using the Roman-style “leafblade” sword to keep them from bending.

Bronze also meant the swords could be longer than copper swords, allowing a

length of 20 to 35-inches, instead of the “short sword” known in the copper

era. By the time of Lehi, swords had achieved lengths of two to four feet in

length during the so-called Iron Age.

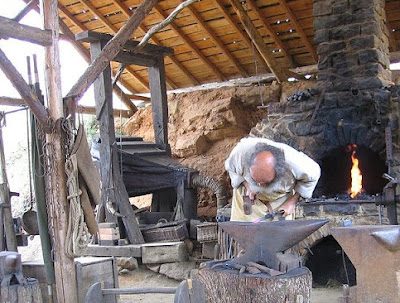

Using

iron in the making of sword blades required a high melting point, which

meant the smelting process limited primitive swordsmiths to the production of a

porous mass of iron called a bloom, which was subsequently hammered out over

the course of numerous heating and cooling cycles to produce the desired blade.

In fact, though iron blades were not much better initially than bronze ones,

iron ore was readily accessible in just about every region of the ancient

world, and while the copper required in the production of bronze was also

abundant, the simplicity in producing workable iron and the relative rarity of

tin meant that iron swords could be produced on a much larger scale, and could

therefore equip more impressive armies.

Now

we don’t know if Nephi ever made an iron blade, or worked with iron, bronze, or

even copper, though living on a farm all his life and requiring knowledge of

fixing and making farm equipment, very possibly involved both Lehi and his sons

in the process. Yet, we see that Nephi was an adept student at both learning

and making things with his hands. And the process of creating steel was

developed quite by accident in the beginning anyway, for it was entirely

unknown what gave steel its valuable properties, and for centuries the techniques

for making high quality steel were closely held, almost alchemical, secrets.

Clearly, iron was its major component, but a myriad of other minor additions

were found empirically, such as adding nickel, vanadium, chromium and

manganese, with even more mysterious treatments evolved for cooling the red hot

object to room temperature.

Much in the way that tin mixed with

copper produces a superior alloy in the form of bronze, adding carbon to iron

in the proper quantities and with the correct technique gives rise to the

vastly superior alloy of steel, though limiting dissolved gasses such as

nitrogen and oxygen, was an issue to be solved.

One of the difficulties of adding

carbon to iron through the techniques of quenching and carbonizing, which first

is a process of hot iron is plunged into cold water, and the second is in

taking heated iron and hammering it and folding it so carbon molecules from the

charcoal was beaten into the iron, which is a decidedly difficult process to control.

This led early swordsmiths working with iron to produce swords of vastly

different qualities from one day to the next, and would have been a perfect

classroom for Nephi, who may well have experimented in metallurgy on his

father’s farm while making tools, repairing cinches, buckles, nails, clench bolts,

etc.

This, of course, is speculation,

but the point is that metal work on ancient farms was both important and indispensable,

and most farmers and farm hands learned rudimentary metal working. And like any

youth, Nephi probably experimented with making himself a knife or two.

This

all leads to Nephi’s record in which he indicated his being impressed with Laban’s

sword—he not only identified it as having pure gold, but fine, precious steel.

How would he have known this had he not had some considerable experience

working with metals?

As we pointed out earlier, Nephi

would likely have known something about metallurgy working on his father’s farm

and the likelihood of any young man from a farm around ancient Jerusalem in

Nephi’s time knowing of such things. Yet, despite this, William J. Hamblin, Professor of History at BYU, in his

article suggests quite the opposite. One can only wonder why.

He begins by trying to lessen the

accuracy of the words used and our understanding of them. As an example, he

tries to make the point that there are linguistic layers involved in the Book

of Mormon and that has an effect on the meaning of the word “steel” used.

According to Hamblin, an historical

Book of Mormon would have at least seven different linguistic layers:

1. Early nineteenth century American

English;

2. Jacobean English of the KJV

Bible;

3. Fourth century A.D. language of

Moroni (Mormon 9.33-34);

4. Mesoamerican language(s);

5. Hebrew of the sixth century B.C.;

6. Egyptian of the sixth century

B.C.;

7. Jaredite language.

First

of all, Hamblin meant Mormon 9:32-33) and Moroni’s comments are simply this: “And now, behold, we have written this record according to our

knowledge, in the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian,

being handed down and altered by us, according to our manner of speech. And if

our plates had been sufficiently large we should have written in Hebrew; but

the Hebrew hath been altered by us also; and if we could have written in

Hebrew, behold, ye would have had no imperfection in our record” (Mormon 9:32-33), which briefly

means that the writers of the Book of Mormon spoke and wrote Hebrew, but used

Reformed Egyptian to write on the Plates (which Joseph Smith translated). Since

they were using a second language to write on the record, he cautioned that

there might be some linguistic mistakes. However, though linguists love to

point this out, they never add the following statement of Moroni when he

qualifies any mistakes the writer has made with: “But

the Lord knoweth the things which we have written, and also that none other

people knoweth our language; and because that none other people knoweth our

language, therefore he hath prepared means for the interpretation thereof”

(Mormon 9:34 ).

That “means” of which Moroni spoke

was Joseph Smith as translator, and the Holy Spirit as the guide to make sure

the translation was correct. Therefore, much of the linguists’ beliefs in

errors and complicated or complex meanings was handled or clarified by the

Spirit in the process of the translation. To understand this “means,” Martin Harris provided a description of the manner

of translating while he was transcribing the Prophet’s translation:

“By aid of the

Seer stone, sentences would appear and were read by the Prophet and written by

Martin, and when finished he would say ‘written;’ and if correctly written, the

sentence would disappear and another appear in its place; but if not written

correctly it remained until corrected, so that the translation was just as it

was engraven on the plates, precisely in the language then used’.” (A Comprehensive History of the Church, Vol.

1, p. 129, emphasis added).

To one and all, this should show

that there would have been no linguistic errors, problems, or complexities to

the translation of the scriptural record of the Book of Mormon other than the

form of English then known and used by the Prophet and the amanuensis (with an

understanding that Joseph’s English in this translation was that of the King

James Bible English); however, every theorist who has to justify his beliefs

and models when they do not agree with what is clearly written in the

scriptural record must provide some explanation to support their difference

from Mormon’s descriptions.

(See

the next post, “Metallurgy Did Not Exist in Mesoamerica

Prior to 600 A.D. – Part VIII,“ to

see how far theorists go to try and bend the facts presented in the scriptural

record to maintain their erroneous beliefs, paradigms and models)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Del,

ReplyDeleteStill haven't heard back on those sources/maps of the Quechua "Land of Many Waters." Really interested in seeing the old maps or sources of that claim.

Thanks!

WonderBoy. Just got back from a ten-day hiatus, will answer shortly.

ReplyDeleteRight on

ReplyDelete